Hua Yan’s Snow on Mount Tian

December 27th, 2007

A 1755 painting by Hua Yan (sometimes considered one of the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou), reproduced in Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting.

Snow on Mount Tian, 1755, Palace Museum, Beijing. Click image for larger version.

The painting “depicts an itinerant merchant trudging through ice and snow in the northern wilderness on a long, arduous journey. Wearing a fur hat and an overcoat, a sword hanging at his waist, he leads a camel. The heads of both the traveler and the camel are raised to the sky as a wild goose flies overhead. The solitary traveler, the camel, and the wild goose give poignancy to the desolation of the scene. But the bleakness of gray sky, brown camel, and white snow are relieved by the overcoat of bright red. Like many poems of the Tang dynasty that describe scenes outside the Great Wall, the picture creates a lonely yet solemn and stirring mood” (p281, Nie Chongzheng’s analysis).

Ernst’s Seven Deadly Elements

December 25th, 2007

Speaking of Rapa Nui, seven collages (mostly cutout illustrations from 19th century French pulp) by Max Ernst from his 1934 pictorial novel, Une semaine de bonté (A Week of Kindness or The Seven Deadly Elements).

Sunday, element of mud (p10).

Monday, element of water (p63).

Tuesday, element of fire (p84).

Wednesday, element of blood (p119).

Thursday, element of blackness (p170).

Friday, element of sight (p181).

Saturday, unknown element (p207).

“And I object to the love of ready-made images in place of images to be made” (Paul Eluard, Comme deux gouttes d’eau, epigraph p180).

Szukalski’s Science of Zermatism

December 23rd, 2007

Eight illustrations by Stanislav Szukalski from Behold!!! The Protong — a sampling of his 39 volume oeuvre on the science of Zermatism.

Szukalski was a polymath who, over a lifetime, developed a science that integrated singular theories in geology (cyclic deluges), anthropology (universal pictographs), linguistics (Protong, a universal first language), zoology (Yeti), anthropolitics (Yetinsyn), with many etceteras. Common to his arguments is an overwhelming accretion of the visual evidence.

“Looking through thousands of illustrated books, I have learned how to SEE. Since childhood I have been addicted to seeing ‘pictures’ in books… I learned not only to look, but really SEE, for I did not know English yet and had to jump to CONCLUSIONS. In fact, I evolved the, to other people unnatural, instinct for UNDERSTANDING things, without knowing what they were. Looking became my life’s OBSESSION. When I am dying I will despair over the fact that I will no more be able to Look and See” (p14).

A sample of Szukalski’s science, on the subject of tribal flood scumlines:

“When the Secondary Globe (the lavaic ocean bottoms) began to submerge in the beginning of the last Farsolar Epoch, the global seas were forced to glide off the Primary (Geologic) Globe. The soil of all the lands that were re-emerging was washed off by the departing seas and the water of the globe became very muddy. In fact, Plato, after visiting Egyptian temples, learned of the chronicles that spoke of the Mediterranan Sea as ‘The Sea of Mud’. Homer’s Iliad was about Ilium (the Latin word for ancient Troy) which in Protong means ‘Mire Remembered’. The state of Illinois, U.S.A. is named after the Illinois River, and in Protong (‘Illi No J(e) Z’) actually means ‘Mire made-Born is From’.

“Wherever the terrified diluvial escapees shored re-emerging lands, their faces were caked with mud. And since each swam differently, each would emerge with individual muddy water ripples across the face. So when they lay there in the mud in the deadly faint, exhausted beyond words, and were found by earlier arrivees on that islet, the facial mud markings were remembered and the Flood Scumlines became the tribal markings. I have an entire volume on these Scumlines with 195 such drawings from every part of the globe” (p31).

Here are a few examples:

A head from Rapa Nui (Easter Island). “The horizontal line [the Flood Scumline] below the nose clearly shows that the ancestor swam to that island in the last Nearsolar Deluge” (p19).

“In Equador and the vicinity of the Panama Canal there are Indians who paint their bodies with black lines emulating the waters in which they stood. They repeat the same lines on their faces, but the topmost of these crosses their noses, just below the eyes. This means that their diluvial ancestor buried his face under the water while swimming and made a stronger stroke with his arms when he came up to get air” (p25).

“This Eskimo’s diluvial ancestor swam with the nostrils under water, coming up to inhale while starting his arm strokes” (p20).

“One of the many funerary jars for holding the ashes of the cremated dead. This one is from prehistoric Poland… Atop the head reposes the cover in the shape of Easter Island. On their necks are many metal necklaces and, as in this one, the image vomits the salt water of the sea. These rings on the neck emulate the water ripples spreading from a drowning person. Usually, there is a large ‘spzilla’ (Polish for ‘pin’) as a Rebus for ‘Z Bi La’ [Protong], which tells us that the person cremated came ‘From Killed (by) Flood’ land and to there was returning” (p22).

“The Chiaco Indian tribe of Equador continue to mark their faces with the Flood Scumline on the very rim of their upper lip” (p20).

“A funerary portrait of a young man drawn from the lid of a large jar that holds the ashes of a cremated man. It was excavated in Italy and dates from the Etruscan period. On the man’s face the ancient tribal Flood Scumline was engraved, crossing his mask just below his nose, emulating a beard. However, the vertical direction of continuous lines tells us that this is really the draining water, heavy with mud.

“The two small circles on the chin and the edge of ripples around them made me turn the drawing upside down and there I saw that the mask resembled the Great Lioness (Easter Island), streaked with sliding-off water as if re-emerging from under the Flood” (p26).

An indication that contemporary Manapes also survived the Deluge:

“Among ancient carvings of the Dorset Culture of the Point Barrow region in Alaska, this mask was discovered which white men assume is an imaginary Devil. But you can plainly see that it is a portrait of a local Sasquatch. Incidentally, in the vertical lines we have a marvelous document. They were carved there to let us know that this creature, like the ancestors of the Alaskan Eskimos, also saved himself from the Deluge, for any lines, vertical or horizontal, represent ‘waters’, hence the Great Flood. There is still another pictograph, besides the vertical draining-off of muddy water. It is the horizontal line just below the nostrils which, by being placed above the water level, tell us that his breath, his SOUL, was saved” (p77).

“Those that saved themselves from drowning, noticed that these creatures also had the fortune to survive, so they named them accordingly, everywhere on this globe in one language, my Protong. The present name Sasquatch was then ‘Sa Z Gladz’, which means ‘Here From Destroyed’ (i.e. the deluged continent)” (p75-6).

All who eagerly perceive the as yet unnamed are vagabonds.

Hazelrigg’s The Sun Book

December 12th, 2007

Two diagrams from John Hazelrigg’s The Sun Book (1916), which reconciles astro-theology, alchemy, and the allegory of Christ.

Man is a “fourfold unit as concerns the elements of his constitution, each of which acts through the threefold essences of his being [Mercury, Sulphur, and Salt; or Spirit, Soul, and Body]; and expressed accordingly each by a triangular symbol, thus: ? Earth, ? Fire, ? Water, ? Air… The field enclosed by the basic lines of these four ideographs is an equilateral square (base of the pyramid), typifying the human cosmos as a reflection of the fourfoldness of the Microcosm. With these folded over, as with an envelope, the apex of each centers at the navel, which is the All-Seeing or Psychic Eye.

“These again are summarized in the… interlaced triangle — the Solomonic Seal — the three lines composing the upright symbol signifying Spirit-fire-air, the masculine trinity; the one inverted is Soul-water-earth, or the feminine trinity; — not separate identities, but differentiations or diverse modes of activity of the One Essence. Combined, these two symbols represent Man-Woman as the substance of the six days of Creation… The seventh day, or the central point equidistant from the six apices of the triangles, signifies not a state of rest, but of equilibrium or repose in the formative processes, and whereat — the investment completed — is inaugurated a new departure in the realms of becoming” (p156-8).

This creation is an allegory for the “interior experiences of every disciple in the path of Initiation. It is thus that the microcosmic system is transformed from a sepulcher of vanities into a tabernacle of divine realities” (p160).

Briefly (too briefly), these six stages are:

1. Nativity, fermentation: “the manifestation of an energy that induces to decomposition, that the elements of bodies may be re-combined in new compounds… that creates a condition of inter-repellence that breaks up and dissolves, to the end of a higher refinement and a more subtle re-arrangement of the relativities, both as concerns physical and spiritual substance” (p161-2). This energy, this vital heat, is the fire of the microcosmic Sun, the Spirit.

2. Baptism, betrothal: of the Soul to the Spirit: a necessary duality: a Divine Marriage between the radical moisture of the microcosmic Moon (Woman) and the vital heat of the microcosmic Sun (Man), whereby the Soul is vivified and may infuse into the Body. Whence the initiate must now confront the four elements of his inner nature.

3. Temptation, earth: “through bodily cleansing the entire structural constitution is gradually metamorphosed and sensitized — the protoplasmic fluids seek new currents — the intermolecular ethers grow more penetrant and corrective in cellular transformations, and the aberrancies and the chimeras that constitute the confusions of the microcosmic wilderness are quelled and corrected through conflict with the sensuous incitements — the sex desires, gluttony, the physical vanities, and the carnalities of the animal nature” (p166).

4. Passion, calcination, fire: the cleansing of the Mind: “here the Higher Will is constrained to do battle with the glamors of Illusion, to overcome the seductive sophistries of Reason, the material Logic that betrays” (p168). “Only in passivity of mind doth the Divine principle express itself” (p174).

5. Gethsemane, dissolution, water: “whence is evolved the intro-vision that feels and knows and does not reason” (p170). This element “claims attention to physical ablution, an important point in connection with which is the fact that the pores of the skin as exhaling media do but represent a function correlative with that of inspiration. In- and out-breathing are not exclusively a specific action of the lungs, for every capillary duct is an avenue of communication with the Universal” (p174).

6. Crucifixion, sublimation, air: “thence through the aeration of the blood the fire at the center of soul is evoked” (p175). “This is the point of Equilibrium” (p172), the “interlaced halves of his being… linked with the Supernal Center” (p176).

“Man is both the artificer and the laboratory. He is the agent and patient, the principle and the personification; he is at once God’s most gifted craftsman and Almighty’s most interesting workshop; he is the Philosopher’s subject-matter, as also the alchemical vase in which it is leavened into holy consistencies — a consortment of perversities and concupiscences, yet a god in the making. He is a circumference, whose center is an altar of divinity where abide the fires of Hestia, whether in abeyance or irradiating forth as the rivers which flowed from out of Eden to water the Garden; for here, housed in clay, guarded by the keepers of the mystical gates, and battlemented with physiological ramparts, is the fabled Eden in which still walk Adam and Eve, as at the dawn of Time; where still crawls the slimy serpent, and where groweth the tree of the knowledge of good and evil” (p147).

Klinger and Disjunctive Unity

December 4th, 2007

Two etchings by Max Klinger collected in the Graphic Works of Max Klinger, with introduction and notes by J. Kirk T. Varnedoe.

“The basic quality in Klinger’s graphic work… could be described by the paradoxical phrase ‘disjunctive unity’. It is a… fundamental principle in his art, extending from the juxtaposition of banal detail and impossible fantasy within the images… to the thematic dichotomy of fantasy and reality… He controls this split, holding it in perpetual poetic tension. Long before the surrealists, he discovered the emotional power of unresolvable disjunction, particularly between levels of reality; through this principle, he formulated another world whose contradictory abnormality had the impact of real experience” (pXXIV).

Four Landscapes: The Road. 1883 (p28). Click for larger version.

“The perspectives of the fence and trees on either side rush to convergence with an unchecked urgency. It is the kind of funneling space found in the psychologically charged vision of Van Gogh, for example, here rendered with a crisp, cool realism that makes it perhaps even more disturbing. The young trees are bound by wire to wooden stake-poles; hence their regimented regularity, and also a certain undercurrent of latent tension, echoed in the ominously leaden sky. The sky… descends slowly from an even light grey at the top of the plate a deep, bass note, darkest and most sinister at the point where the road hurtles into deep space” (p81).

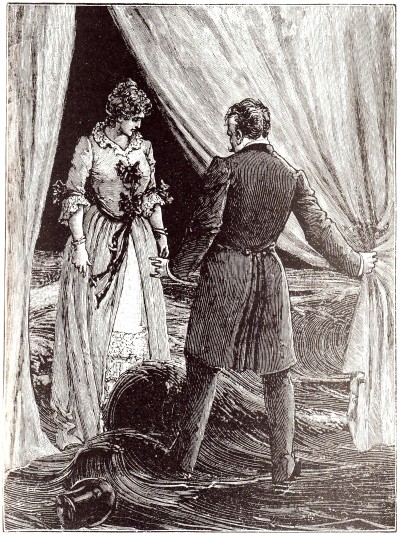

Dramas: In Flagranti. 1883 (p38). Click for larger version.

“The Latin title, related to the traditional phrase flagrante delicto, means ‘caught in the act’. The act here was one of adultry, a woman meeting her lover on a moonlit terrace. Her husband, leaning out of the upstairs window, has just shot the lover, whose feet sprawl out from behind the balustrade. The report of the shot still seems to hang in the air, as birds swirl away in fright and the woman clutches her ears in horror. The terror of the scene is intensified by Klinger’s understatement: the moment of maximum violence has just passed, the agony of the dead man is only hinted at, and the whole scene is slowed to an eerie suspension by the obsessive detailing of the ornate villa and the dense plant growth” (p83).