Florensky on Gold

March 19th, 2008

Three more icons (see previous post), and Florensky (again, from Iconostasis) on the use of gold-leaf in iconpainting.

![]()

The Holy Face (The Vernicle) icon, 16th century.

“The whole of iconpainting seeks to prove — with an ultimate persuasiveness — that the gold and the paint are wholly incommensurable. The happiest icon attains this, for in its gold we can discern not the slightest dullness or darkness or materiality. The gold is pure, ‘admixtureless’ light, a light impossible to put on the same plane with paint — for paint, as we plainly see, reflects the light: thus, the paint and the gold, visually apprehended, belong to wholly different sphere of existence. Gold is therefore not a color but a tone” (p123).

“Depicting this unmingling mingling is the representation of the invisible dimension of the visible, the invisible understood now in the highest and ultimate meaning of the word as the divine energy that penetrates into the visible so that we can see it” (p127).

![]()

Archangel Michael icon, 14th century.

“In the iconpainting process, the golden color of superqualitative existence first surrounds the areas that will become the figures, manifesting them as possibilities to be transfigured so that the abstract non-existents become concrete non-existents; i.e., through the gold, the figures become potentialities. These potentialities are no longer abstract, but they do not yet have distinct qualities, although each of them is a possibility of not any but of some concrete quality. The non-existent has become the potential. Technically speaking, the operation is one of filling in with color the spaces defined by the golden contours so that the abstract white silhouette becomes the concrete colorful silhouette of the figure — more precisely, it begins to become the concrete colorful silhouette of the figure. For at this point, the space does not yet posses true color; rather, it is only not a darkness, not wholly a darkness, having now the first gleam of light, the first shimmer of existence out from the dark nothingness. This is the first manifestation of the quality, color, a little bit illumined by light… Reality is revealed by the degrees of the manifestation of existence” (p138).

![]()

St. John the Baptist icon, 15th century.

“I call your attention to this remarkable sentence: the icon is executed upon light — a sentence perfectly expressing the whole ontology of iconpainting. When it corresponds most closely to iconic tradition, light shines golden, i.e., it is pure light and not color. In other words, every iconic image appears always in a sea of golden grace, ceaselessly awash in the waves of divine light. In the heart of this light ‘we live, and move, and have our being’; it is the space of true reality. Thus, we can comprehend why golden light is the icon’s true measure: any color would drag the icon to earth and weaken its whole vision” (p136-7).

Florensky’s Iconostasis

March 15th, 2008

Three Orthodox icons, the painting of which is described in Pavel Florensky‘s Iconostasis. Thanks go to Polymathicus for recommending this essential text.

![]()

Archangel Gabriel icon, 16th century.

“In creating a work of art, the psyche or soul of the artist ascends from the earthly realm into the heavenly; there, free of all images, the soul is fed in contemplation by the essences of the highest realm, knowing the permanent noumena of things; then, satiated with this knowing, it descends again to the earthly realm. And precisely at the boundary between the two worlds, the soul’s spiritual knowledge assumes the shapes of symbolic imagery: and it is these images that make permanent the work of art. Art is thus the materialized dream, separated from the ordinary consciousness of waking life.

“In this separation, there are two moments that yield, in the artwork, two types of imagery: the moment of ascent into the heavenly realm, and the moment of descent into the earthly world. At the crossing of the boundary into the upper world, the soul sheds — like outworn clothes — the images of our everyday emptiness, the psychic effluvia that cannot find a place above, those elements of our being that are not spiritually grounded. At the point of descent and re-entry, on the other hand, the images are experiences of mystical life crystallized out on the boundary of two worlds. Thus, an artist misunderstands (and so causes us to misunderstand) when he puts into his art those images that come to him during the uprushing of his inspiration — if, that is, it is only the imagery of the soul’s ascent. We need, instead, his early morning dreams, those dreams that carry the coolness of the eternal azure. The other imagery is merely psychic raw material, no matter how powerfully it affects him (and us), no matter how artistically and tastefully developed in the artwork. Once we understand this difference, we can easily distinguish the ‘moment’ of an artistic image: the descending image, even if incoherently motivated in the work, is nevertheless abundantly teleological; hence, it is a crystal of time in an imaginal space. The image of ascent, on the other hand, even if bursting with artistic coherence, is merely a mechanism constructed in accordance with the moment of its psychic genesis. When we pass from ordinary reality into the imagined space, naturalism generates imaginary portrayals whose similarity to everyday life creates an empty image of the real. The opposite art — symbolism — born of the descent, incarnates in real images the experience of the highest realm; hence, this imagery — which is symbolic imagery — attains a super-reality” (p44-5).

![]()

Black Madonna of Czestochowa icon, 14th century.

“Icons, as St. Dionysus Aeropagite says, are ‘visible images of mysterious and supernatural visions.’ An icon is therefore always either more than itself in becoming for us an image of a heavenly vision or less than itself in failing to open our consciousness to the world beyond our senses — then it is merely a board with some paint on it. Thus, the contemporary view that sees iconpainting as an ancient fine art is profoundly false. It is false, first of all, because the very assumption that a fine art possesses its own intrinsic power is, in itself, false: a fine art is either greater or less than itself. Any instance of fine art (such as a painting) reaches its goal when it carries the viewer beyond the limitations of empirically seen colors on canvas and into a specific reality, for a painting shares with all symbolic work the basic ontological characteristic of seeking to be that which it symbolizes. But if a painter fails to attain this end, either for a specific group of viewers or for the world in general, so that his painting leads no one beyond itself, then his work unquestionably fails to be art; we then call it mere daubs of paint, and so on. Now, an icon reaches its goal when it leads our consciousness out into the spiritual realm where we behold ‘mysterious and supernatural visions.’ If this goal is not reached — if neither the steadily empathic gaze nor the swiftly intuitive glance evokes in the viewer the reality of the other world (as the pungent scent of seaweed in the air evokes in us the still faraway ocean), then nothing can be said of that icon except that it has failed to enter into the works of spiritual culture and that its value is therefore either merely material or (at best) archaeological” (p65-6).

![]()

Prophet Elijah icon, 15th century.

“Both metaphysics and iconpainting are grounded on the same rational fact (or factual rationality) concerning a spiritual appearance: which is that, in anything sensuously given, the senses wholly penetrate it in such a way that the thing has nothing abstract in it but is entirely incarnated sense and comprehended visuality. A Christian metaphysician will therefore never lose concreteness and so, for him, an icon is always sensuously given; equally, the iconpainter can never employ a visual technique that has no metaphysical sensuousness. But the fact that the Christian philosopher consciously compares iconpainting and ontology does not lead the iconpainter to use the philosopher’s terms; rather, the iconpainter expresses Christian ontology not through a study of its teachings but by philosophizing with his brush. It is no accident that the supreme masters of iconpainting were, in the ancient texts, called philosophers; for, although they did not write a single abstract word, these masters (illumined by divine vision) testified to the incarnate Word with their hands and fingers, philosophizing truly through their colors” (p152).

Stolcius on the Stone

March 2nd, 2008

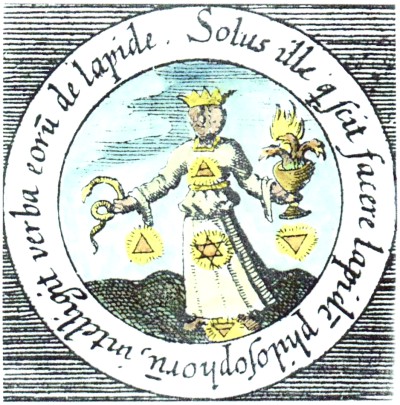

Four emblems from The Hermetic Garden of Daniel Stolcius. This 1620 collection includes 160 emblems appearing in Mylius‘s Opus Medico Chymicum, each accompanied by a four line Latin verse composed by Stolcius. The present edition was hand-colored and -made by Adam McLean.

The selection of emblems below concerns the Philosophical Stone.

Emblem 27: Mitigo, the Philosopher.

However men and beasts despise the Stone, yet it is loved by the wise.

However men and beasts trample the Stone,

It still takes no notice of them all.

For only at the hands of philosophers is it investigated;

These it loves and delights in them especially.

Emblem 62: Author of the Philosophical Rhymes.

You shall visit the interior of the Earth.

He who seeks the Stone shall search the interior of the Earth.

And there shall find where the Medicine lies hidden,

There recognize the many headed Dragon,

There see what may become the Lion by our Art.

Emblem 100: Petrus, Monk and Philosopher.

The fiery little light lives in the Earth, and water cannot extinguish it, for it is heavenly.

This heavenly radiance is hidden in caverns in the ground.

Yet still the moist wave cannot put it out.

Seek it. Revolve the whole world, like Atlas, in your mind.

Perhaps you will find it.

Emblem 107: Hortulanus, Philosopher and Chemist.

Only he who knows how to make the Philosopher’s Stone, understands what they say concerning the Stone.

Only he who knows how to produce our Stone,

Hears the mystic words of the hidden chorus.

Then, in the amazing, different cycle of the Elements, he perceives,

And obtains by entreaty, the longed for riches of Hermogenes.