Enard and the Quality of Attention

August 23rd, 2008

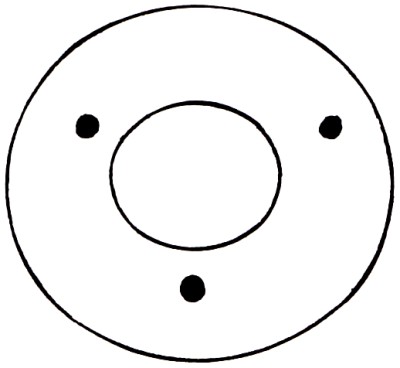

A painting by André Enard appearing in An Art of Our Own by Roger Lipsey.

Number 27, 1975, oil and goldleaf on wood (black-and-white reproduction).

“What are we looking at? A geometry that recalls both the Platonic ‘perfect figures’ and Tantric designs, the image of the labyrinth rendered as a looping intestinal pattern, gestational images of seed and egg — drawn into a whole by craftsmanship that brings to mind the skills of jeweler and icon-maker” (Lipsey, p414).

Enard writes, in a 1987 letter to the author, “Most manifestations of art today lack good common sense, lack relation with a higher reality, and lack spiritual purpose.

“What can there be of value without a search into oneself, linked to essential knowledge?

“Isn’t the ultimate desire of human beings to perceive an order of laws that surpasses us yet is also within us, and to participate in that order?

“Isn’t the role of the artist to reflect on and to reflect back something of this greater order, for the sake of stimulating the viewer to reconstruct the original idea?

“Isn’t this quest the purpose, conscious or unconscious, of all artistic effort?

“To try to grasp the soul, that which animates each thing at its source!

“Finally, what seems most important in the process of painting is the quality of feeling that the artist conveys by doing what he does, no matter what subject he chooses; and then, the care he takes and the quality of attention he communicates, which may arouse the same quality in the viewer.

“When that quality of energy is there, it can be felt — it is palpable, visible in the canvas. It has an action; one is touched, and one can glimpse the reality behind appearances.

“The act of painting can be understood as an act of contemplation, of meditation, through which the artist can rediscover and remember what is laid down in his deepest nature, his primal consciousness — and by that very means summon the same in response from the viewer” (p415-6).

Tantra Art as Psychic Matrix

August 16th, 2008

Four images from Mookerjee’s The Tantric Way (see also these yantras).

“Tantra is a creative mystery which impels us to transmute our actions more and more into inner awareness: not by ceasing to act but by transforming our acts into creative evolution. Tantra provides a synthesis between spirit and matter to enable man to achieve his fullest spiritual and material potential. Renunciation, detachment and asceticism — by which one may free oneself from the bondage of existence and thereby recall one’s original identity with the source of the universe — are not the way of tantra. Indeed, tantra is the opposite: not a withdrawal from life, but the fullest possible acceptance of our desires, feelings, and situations as human beings.

“Tantra has healed the dichotomy that exists between the physical world and its inner reality, for the spiritual, to a tantrika, is not in conflict with the organic but rather its fulfillment. His aim is not the discovery of the unknown but the realization of the known, for ‘What is here, is everywhere. What is not here, is nowhere’ (Visvasara Tantra); the result is an experience which is even more real than the experience of the objective world” (p9).

Gunas: sattva, rajas, tamas (p95).

Tantra art “is specially intended to convey a knowledge evoking a higher level of perception, and taps dormant sources of our awareness. This form of expression is not pursued like detached speculation to achieve aesthetic delight, but has a deeper meaning. Apart from aesthetic value, its real significance lies in its content, the meaning it conveys, the philosophy of life it unravels, the world-view it represents. In this sense tantra art is visual metaphysics” (p41).

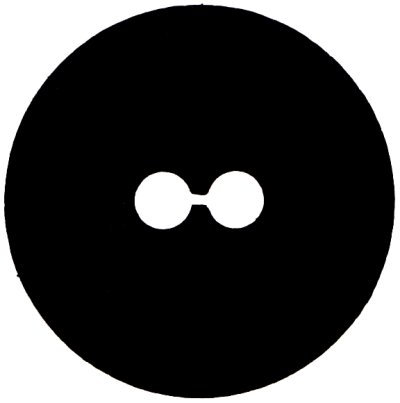

Shyama (Kali) Yantra. Rajasthan, 18th century (p35).

Yantra “represents an energy pattern whose force increases in proportion to the abstraction and precision of the diagram. Through these power-diagrams creation and control of ideas are said to be possible” (p34).

The Principle of Fire. Rajasthan, 18th century (p189).

“Tantric images have a meditative resilience expressed mostly in abstract signs and symbols. Vision and contemplation serve as a basis for the creation of free abstract structures surpassing schematic intention. A geometrical configuration such as a triangle representing Prakriti or female energy, for example, is neither a reproduced image nor a confused blur of distortion but a primal root-form representing the governing principle of life in abstract imagery as a sign” (p44).

Salagram, a cosmic spheroid (p13).