Florensky on Gold

March 19th, 2008

Three more icons (see previous post), and Florensky (again, from Iconostasis) on the use of gold-leaf in iconpainting.

![]()

The Holy Face (The Vernicle) icon, 16th century.

“The whole of iconpainting seeks to prove — with an ultimate persuasiveness — that the gold and the paint are wholly incommensurable. The happiest icon attains this, for in its gold we can discern not the slightest dullness or darkness or materiality. The gold is pure, ‘admixtureless’ light, a light impossible to put on the same plane with paint — for paint, as we plainly see, reflects the light: thus, the paint and the gold, visually apprehended, belong to wholly different sphere of existence. Gold is therefore not a color but a tone” (p123).

“Depicting this unmingling mingling is the representation of the invisible dimension of the visible, the invisible understood now in the highest and ultimate meaning of the word as the divine energy that penetrates into the visible so that we can see it” (p127).

![]()

Archangel Michael icon, 14th century.

“In the iconpainting process, the golden color of superqualitative existence first surrounds the areas that will become the figures, manifesting them as possibilities to be transfigured so that the abstract non-existents become concrete non-existents; i.e., through the gold, the figures become potentialities. These potentialities are no longer abstract, but they do not yet have distinct qualities, although each of them is a possibility of not any but of some concrete quality. The non-existent has become the potential. Technically speaking, the operation is one of filling in with color the spaces defined by the golden contours so that the abstract white silhouette becomes the concrete colorful silhouette of the figure — more precisely, it begins to become the concrete colorful silhouette of the figure. For at this point, the space does not yet posses true color; rather, it is only not a darkness, not wholly a darkness, having now the first gleam of light, the first shimmer of existence out from the dark nothingness. This is the first manifestation of the quality, color, a little bit illumined by light… Reality is revealed by the degrees of the manifestation of existence” (p138).

![]()

St. John the Baptist icon, 15th century.

“I call your attention to this remarkable sentence: the icon is executed upon light — a sentence perfectly expressing the whole ontology of iconpainting. When it corresponds most closely to iconic tradition, light shines golden, i.e., it is pure light and not color. In other words, every iconic image appears always in a sea of golden grace, ceaselessly awash in the waves of divine light. In the heart of this light ‘we live, and move, and have our being’; it is the space of true reality. Thus, we can comprehend why golden light is the icon’s true measure: any color would drag the icon to earth and weaken its whole vision” (p136-7).

Florensky’s Iconostasis

March 15th, 2008

Three Orthodox icons, the painting of which is described in Pavel Florensky‘s Iconostasis. Thanks go to Polymathicus for recommending this essential text.

![]()

Archangel Gabriel icon, 16th century.

“In creating a work of art, the psyche or soul of the artist ascends from the earthly realm into the heavenly; there, free of all images, the soul is fed in contemplation by the essences of the highest realm, knowing the permanent noumena of things; then, satiated with this knowing, it descends again to the earthly realm. And precisely at the boundary between the two worlds, the soul’s spiritual knowledge assumes the shapes of symbolic imagery: and it is these images that make permanent the work of art. Art is thus the materialized dream, separated from the ordinary consciousness of waking life.

“In this separation, there are two moments that yield, in the artwork, two types of imagery: the moment of ascent into the heavenly realm, and the moment of descent into the earthly world. At the crossing of the boundary into the upper world, the soul sheds — like outworn clothes — the images of our everyday emptiness, the psychic effluvia that cannot find a place above, those elements of our being that are not spiritually grounded. At the point of descent and re-entry, on the other hand, the images are experiences of mystical life crystallized out on the boundary of two worlds. Thus, an artist misunderstands (and so causes us to misunderstand) when he puts into his art those images that come to him during the uprushing of his inspiration — if, that is, it is only the imagery of the soul’s ascent. We need, instead, his early morning dreams, those dreams that carry the coolness of the eternal azure. The other imagery is merely psychic raw material, no matter how powerfully it affects him (and us), no matter how artistically and tastefully developed in the artwork. Once we understand this difference, we can easily distinguish the ‘moment’ of an artistic image: the descending image, even if incoherently motivated in the work, is nevertheless abundantly teleological; hence, it is a crystal of time in an imaginal space. The image of ascent, on the other hand, even if bursting with artistic coherence, is merely a mechanism constructed in accordance with the moment of its psychic genesis. When we pass from ordinary reality into the imagined space, naturalism generates imaginary portrayals whose similarity to everyday life creates an empty image of the real. The opposite art — symbolism — born of the descent, incarnates in real images the experience of the highest realm; hence, this imagery — which is symbolic imagery — attains a super-reality” (p44-5).

![]()

Black Madonna of Czestochowa icon, 14th century.

“Icons, as St. Dionysus Aeropagite says, are ‘visible images of mysterious and supernatural visions.’ An icon is therefore always either more than itself in becoming for us an image of a heavenly vision or less than itself in failing to open our consciousness to the world beyond our senses — then it is merely a board with some paint on it. Thus, the contemporary view that sees iconpainting as an ancient fine art is profoundly false. It is false, first of all, because the very assumption that a fine art possesses its own intrinsic power is, in itself, false: a fine art is either greater or less than itself. Any instance of fine art (such as a painting) reaches its goal when it carries the viewer beyond the limitations of empirically seen colors on canvas and into a specific reality, for a painting shares with all symbolic work the basic ontological characteristic of seeking to be that which it symbolizes. But if a painter fails to attain this end, either for a specific group of viewers or for the world in general, so that his painting leads no one beyond itself, then his work unquestionably fails to be art; we then call it mere daubs of paint, and so on. Now, an icon reaches its goal when it leads our consciousness out into the spiritual realm where we behold ‘mysterious and supernatural visions.’ If this goal is not reached — if neither the steadily empathic gaze nor the swiftly intuitive glance evokes in the viewer the reality of the other world (as the pungent scent of seaweed in the air evokes in us the still faraway ocean), then nothing can be said of that icon except that it has failed to enter into the works of spiritual culture and that its value is therefore either merely material or (at best) archaeological” (p65-6).

![]()

Prophet Elijah icon, 15th century.

“Both metaphysics and iconpainting are grounded on the same rational fact (or factual rationality) concerning a spiritual appearance: which is that, in anything sensuously given, the senses wholly penetrate it in such a way that the thing has nothing abstract in it but is entirely incarnated sense and comprehended visuality. A Christian metaphysician will therefore never lose concreteness and so, for him, an icon is always sensuously given; equally, the iconpainter can never employ a visual technique that has no metaphysical sensuousness. But the fact that the Christian philosopher consciously compares iconpainting and ontology does not lead the iconpainter to use the philosopher’s terms; rather, the iconpainter expresses Christian ontology not through a study of its teachings but by philosophizing with his brush. It is no accident that the supreme masters of iconpainting were, in the ancient texts, called philosophers; for, although they did not write a single abstract word, these masters (illumined by divine vision) testified to the incarnate Word with their hands and fingers, philosophizing truly through their colors” (p152).

Solaris by Bertrandt

February 24th, 2008

Andrzej Bertrandt’s 1972 Polish movie poster for Tarkovsky‘s adaptation of Lem‘s Solaris.

Click for full version. From Nostalghia‘s complete collection of Solaris movie posters.

Dali’s 45th Secret

February 16th, 2008

Four drawings by Salvador Dali from his 1948 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship.

Isocahedron, p109.

“Know at once that among the most inexplicable secrets of nature and of creation is that which rules that the number of five governs the animal and vegetable world, that is to say, the organic world, but that on the other hand never, never does this number of five occur in the mineral or inorganic world. So that if the pentagon must become for you the archetypal figure, since in your painting you must express without discontinuity only the quintessence of the organic, the hexagon on the contrary must be considered by you the prototype of your antitype, as well as all its derived crystallizations which are the inorganic ones of the mineral realm.

“You have thus just understood, in learning this, the profound reason of what your painter’s intuition had so surely revealed to you when you confessed to me that you had always detested without knowing why the decorative charm of crystallizations, and especially the congealed, blind, additioned and arithmetical ones of snow. If you do not like them, and are so right in not liking them, it is because your art of painting is exactly the contrary of decorative art, since it is — as you now know — a cognitive art” (p168-9).

Sea urchin, p174.

“I shall… enlighten you without wasting a moment as to Secret Number 45, which concerns the aesthetic virtues of… the sea urchin, in which all the magic splendors and virtues of pentagonal geometry are found resolved, a creature weighted with royal gravity and which does not even need a crown for, being a drop held in perfect balance by the surface tension of its liquid, it is world, cupola and crown at one and the same time, hence universe!

“Bow your head, now, toward the depths of those other celestial abysses of the white calms of the Mediterranean Sea and pull out a sea urchin and accustom yourself to considering the entire universe through the geometric quintessence of its teeth, which form a kind of cosmogonic and pentagonal flower in its lower orifice where is lodged its chewing apparatus, called ‘Aristotle’s lantern’… Painter, take my advice: keep even beside your easel or somewhere close to your work a sea urchin’s skeleton, so that its little weight may serve by its sole presence in your meditations, just as the weight of a human skull attends at every moment those of saints and anchorites. For the latter, since they lived constantly in their ecstasies and celestial ravishments, required the presence of the skull which, like the ballast, held them to their earthly and human condition; while you, painter, live only in those other ecstasies and ravishments which are given to you, on the contrary, by matter and its viscosity. And you will need that blue-tinged skeleton of the sea urchin which, by its lack of weight, will constantly remind you of the celestial regions which the sensuality of your oils and your media might so easily cause you to forget. Thus the mystic who lives only in the celestial paradise bears in his hand a terrestrial skeleton: the skull of man; while the painter who is an Epicurean — for even if he is often a Stoic in his work, he never ceases to live in terrestrial paradises — must bear in his hand the sea urchin, which is like the very skeleton of heaven” (p175-6).

Painter and saint, p174.

“For remember once more that the painter’s head has already been adequately compared, successively and in each of these four chapters to an oil lamp which gives light, to the hump of a ruminant whose mouth is like the eye of a lamp which gives light, to a Bernard hermit who lives within the shell of your skull, and whose red teeth are the arms of the painter which, like a flame of light, also illuminate the picture. And now to give you even more pleasure, I shall without more ado compare this same painter’s head, not to a Bernard the hermit but to a miller who is also, like yourself, a kind of hermit who ruminates and masticates and grinds in the mill of his brain which is the storehouse and attic of reserve images of the camel’s hump; in which the grain of intelligence lies piled, that luminous quintessence, that flow of wheat which is the whiteness of the earth with which you are to knead that daily bread of painting, which thus becomes again the prayer which the painter, with his flour which is the terrestrial luminosity of this world below, daily lifts toward the celestial luminosities of the above. For all the mystery and miraculous humble aspiration of the man painter is nothing less than to make light, radiant and divine, with white and earth colors which are dull and sere” (p150).

Young and adult sea urchin, p108.

Campbell on the Hero’s Deed

January 29th, 2008

Three illustrations from Joseph Campbell’s The Power of Myth.

“There’s a very interesting statement about the origin of the Grail. One early writer says that the Grail was brought from heaven by the neutral angels. You see, during the war in heaven between God and Satan, between good and evil, some angelic hosts sided with Satan and some with God. The Grail was brought down through the middle by the neutral angels. It represents that spiritual path that is between pairs of opposites, between fear and desire, between good and evil” (p195-6).

Angels carrying grail, The Playfair Book of Hours, fifteenth century (p196).

Another [source for the Holy Grail] “is that there is a cauldron of plenty in the mansion of the god of the sea, down in the depths of the unconscious. It is out of the depths of the unconscious that the energies of life come to us. This cauldron is the inexhaustible source, the center, the bubbling spring from which all life proceeds… [It is] not only the unconscious but also the vale of the world. Things are coming to life around you all the time. There is a life pouring into the world, and it pours from an inexhaustible source” (p217).

Jonah the whale.

“When life comes into being, it is neither afraid nor desiring, it is just becoming. Then it gets into being, and it begins to be afraid and desiring. When you can get rid of fear and desire and just get back to where you’re becoming, you’ve hit the spot” (p218).

“The Grail becomes symbolic of an authentic life that is lived in terms of its own volition, in terms of its own impulse system, that carries itself between the pairs of opposites of good and evil, light and dark” (p197).

The fire-theft. Valeriano, Hieroglyphica, 1586 (p128).

“Many visionaries and even leaders and heroes [are] close to the edge of neuroticism… They’ve moved out of the society that would have protected them, and into the dark forest, into the world of fire, of original experience. Original experience has not been interpreted for you, and so you’ve got to work out your life for yourself. Either you can take it or you can’t. You don’t have to go far off the interpreted path to find yourself in very difficult situations. The courage to face the trials and to bring a whole new body of possibilities into the field of interpreted experiences for other people to experience — that is the hero’s deed” (p41).

Szukalski on Thinking

January 20th, 2008

A drawing by Szukalski (see previous post), reproduced in his Inner Portraits.

The Ancestral Helmet, 1940.

“Just another careful ‘silly notion’ that gave me an excuse to do my best. Get in the habit to work with utmost concentration and you will be THE BEST. We scream piercingly when born, yet may become dumb mutes from never making an effort to COMMUNICATE. It is the effort that gives us the vertical posture and creative thinking. Crawl on your knees in an effort to walk your own paths and you will become a thinking person who will be able to bring original values, never perceived before, for within each one of us there is a separate universe of yet uncreated Gifts.

“Those who are well educated may well be mere apes that have learned the ways of Humans, but who cannot think; misled simpletons bedressed with other birds’ features. To think is to be ORIGINAL. Those who follow their own council, lead themselves upward, for their thinking is bewinged” (p28).

Hua Yan’s Snow on Mount Tian

December 27th, 2007

A 1755 painting by Hua Yan (sometimes considered one of the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou), reproduced in Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting.

Snow on Mount Tian, 1755, Palace Museum, Beijing. Click image for larger version.

The painting “depicts an itinerant merchant trudging through ice and snow in the northern wilderness on a long, arduous journey. Wearing a fur hat and an overcoat, a sword hanging at his waist, he leads a camel. The heads of both the traveler and the camel are raised to the sky as a wild goose flies overhead. The solitary traveler, the camel, and the wild goose give poignancy to the desolation of the scene. But the bleakness of gray sky, brown camel, and white snow are relieved by the overcoat of bright red. Like many poems of the Tang dynasty that describe scenes outside the Great Wall, the picture creates a lonely yet solemn and stirring mood” (p281, Nie Chongzheng’s analysis).

Ernst’s Seven Deadly Elements

December 25th, 2007

Speaking of Rapa Nui, seven collages (mostly cutout illustrations from 19th century French pulp) by Max Ernst from his 1934 pictorial novel, Une semaine de bonté (A Week of Kindness or The Seven Deadly Elements).

Sunday, element of mud (p10).

Monday, element of water (p63).

Tuesday, element of fire (p84).

Wednesday, element of blood (p119).

Thursday, element of blackness (p170).

Friday, element of sight (p181).

Saturday, unknown element (p207).

“And I object to the love of ready-made images in place of images to be made” (Paul Eluard, Comme deux gouttes d’eau, epigraph p180).

Klinger and Disjunctive Unity

December 4th, 2007

Two etchings by Max Klinger collected in the Graphic Works of Max Klinger, with introduction and notes by J. Kirk T. Varnedoe.

“The basic quality in Klinger’s graphic work… could be described by the paradoxical phrase ‘disjunctive unity’. It is a… fundamental principle in his art, extending from the juxtaposition of banal detail and impossible fantasy within the images… to the thematic dichotomy of fantasy and reality… He controls this split, holding it in perpetual poetic tension. Long before the surrealists, he discovered the emotional power of unresolvable disjunction, particularly between levels of reality; through this principle, he formulated another world whose contradictory abnormality had the impact of real experience” (pXXIV).

Four Landscapes: The Road. 1883 (p28). Click for larger version.

“The perspectives of the fence and trees on either side rush to convergence with an unchecked urgency. It is the kind of funneling space found in the psychologically charged vision of Van Gogh, for example, here rendered with a crisp, cool realism that makes it perhaps even more disturbing. The young trees are bound by wire to wooden stake-poles; hence their regimented regularity, and also a certain undercurrent of latent tension, echoed in the ominously leaden sky. The sky… descends slowly from an even light grey at the top of the plate a deep, bass note, darkest and most sinister at the point where the road hurtles into deep space” (p81).

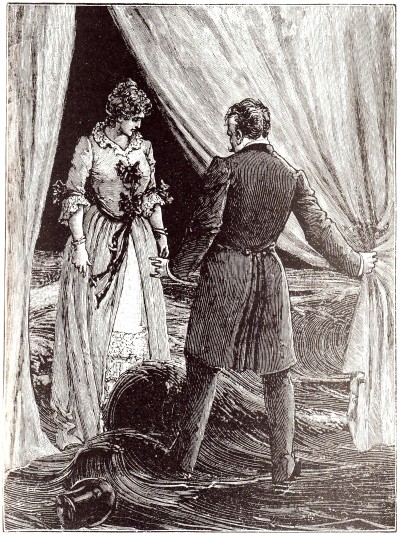

Dramas: In Flagranti. 1883 (p38). Click for larger version.

“The Latin title, related to the traditional phrase flagrante delicto, means ‘caught in the act’. The act here was one of adultry, a woman meeting her lover on a moonlit terrace. Her husband, leaning out of the upstairs window, has just shot the lover, whose feet sprawl out from behind the balustrade. The report of the shot still seems to hang in the air, as birds swirl away in fright and the woman clutches her ears in horror. The terror of the scene is intensified by Klinger’s understatement: the moment of maximum violence has just passed, the agony of the dead man is only hinted at, and the whole scene is slowed to an eerie suspension by the obsessive detailing of the ornate villa and the dense plant growth” (p83).

Zhu Derun on Primordial Chaos

November 30th, 2007

A 1349 painting by Zhu Derun, reproduced in Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting.

Hunlu tu [Primordial Chaos], handscroll, ink on paper, p163. Click image for larger version.

James Cahill describes the painting: “Hunlun refers to the great undifferentiated matter out of which the cosmos was formed, and the philosophical intent of the work is stated in Zhu’s inscription, which takes the form of a brief essay on this Daoist cosmological concept. Hunlun, he writes, is not square but round, not round but square. Before the appearance of heaven and earth there were no forms, and yet forms existed; after the appearance of heaven and earth forms existed, but their constant expansion and contraction, or unfurling and furling, makes them beyond measuring.

“The work, in keeping with this theme, is part picture, part cosmic diagram. The objects in it represent, among other things, states of transformation, or rates of growth and decay: very slow in the earth and rock, somewhat faster in the pine, faster still in the wind-blown, ‘unfurling’ vines. One might be tempted to read the circle at the right as another symbol of change, the inconstant moon, or its reflection in the water, but it is too large and too abstract to encourage that reading and must in some way represent the circular hunlun itself… The drawing of the swirling vines seems also to have loosened itself from representation and entered the realm of the abstract and diagrammatic. One could also see Zhu Derun’s rendering of the bank, rock, pine, and grasses as similarly driven more by brush momentum than by attention to forms” (p163).