The Scholar Immortal

June 6th, 2007

16th century Chinese painting, split into left and right halves, appearing in Alasdair Clayre’s 1984 The Heart of the Dragon.

Left half: floating immortal. Click for larger version.

Right half: sleeping scholar. Click for larger version.

“In a 16th-century painting illustrating a Daoist poem, a scholar asleep in his thatched cottage dreams he is an immortal, floating over the mountains” (p47).

Itten and Phantasmagorical Resonance

March 9th, 2007

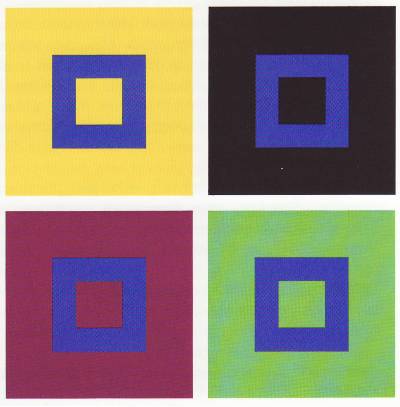

Three figures from Johannes Itten‘s The Elements of Color, 1961.

“Colors of equal brilliance” (p39).

“The doctrine to be developed here is an aesthetic color theory originating in the experience and intuition of a painter. For the artist, effects are decisive, rather than agents as studied by physics and chemistry. Color effects are in the eye of the beholder. Yet the deepest and truest secrets of color effect are, I know, invisible even to the eye, and are beheld by the heart alone. The essential eludes conceptual formulation” (p7).

“Combinations showing how the same blue… [is] altered in expression by different juxtaposed colors” (p87).

“Symbolism without visual accuracy and without emotional force would be mere anemic formalism; visually impressive effect without symbolic verity and emotional power would be banal imitative naturalism; emotional effect without constructive symbolic content or visual strength would be limited to the plane of sentimental expression” (p13).

“Harmonious proportions of areas for complementary colors” (p60).

“Doctrines and theories are best for weaker moments. In moments of strength, problems are solved intuitively, as if of themselves” (p7).

Fe Fi Fo Fum and Apothegmatical Pedantry

February 24th, 2007

Two illustrations reprinted in Iona and Peter Opie’s The Classic Fairy Tales (1974). From a 1794 edition of Tommy Thumb’s Song Book, for all little Masters and Misses (p63), we see the giant’s refrain:

Then, in The History of Tom Thumbe (1621 edition), from the “gyant” while searching for Tom (p40):

Now fi, fee, fau, fan,

I feele smell of a dangerous man:

Be he alive, or be he dead,

Ile grind his bones to make me bread.

Onto Jack the Giant Killer (1761 edition, p63):

Fee, fau, fum,

I smell the blood of an English man,

Be he alive, or be he dead,

I’ll grind his bones to make my bread.

The Opies footnote the pattern as “perhaps the most famous war cry in English literature” (p63), common to British tales of giants and ogres, in numerous versions, such as:

Fe, fi, fo, fum,

I smell the blood of an Englishman;

If he have any liver and lights

I’ll have them for my supper tonight.

But as to its origins? Thomas Nashe cautions in Haue with You to Saffrom-Walden (1596, p48):

O, tis a precious apothegmaticall Pedant, who will finde matter inough to dilate a whole daye of the first inuention of Fy, fa, fum, I smell the bloud of an Englishman.

Which brings to mind this woodcut from an 1840 edition of Jack the Giant Killer (p59):

Still, leaving Opie, a two-part footnote in Jacobs’ English Fairy Tales (p152) tantalizes. First, in the 1889 The Folk-tales of the Magyars, Kriza et al. review cross-cultural olfactory keenness of folk creatures, and include this elf king’s version (p341):

With fi, fe, fa, and fum,

I smell the blood of a Christian man,

Be he dead, be he living, with my brand,

I’ll clash his harns frae his harns pan.

Then, in his introduction to Perrault’s Popular Tales (pCVI/II), Lang traces the blood-scent archetype back to at least Aeschylus’ Eumenides from 458 BC, wherein the Furies trace the scent of Orestes (“The smell of human blood gives me a smiling welcome” (l252))—although their apothegms miss apophony.