German Expressionist Woodcuts

July 16th, 2007

Four woodcuts from German Expressionist Woodcuts, 1994, edited by Shane Weller.

“Expressionism was in part a reaction against Impressionism‘s emphasis on atmospherics and surface appearances, and against academic painting’s rigid technique, stressing instead the emotional state of the artist and subject… creating an experience rich in drama that conveyed the inner reality of the subject matter” (pvii).

Ernst Barlach. To Joy, 1927 (p1).

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Three Paths, 1917 (p47).

Christian Rohlfs. Large Head, 1922 (p100).

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Prophetess, 1919 (p115).

Wither’s Collection of Emblems

July 14th, 2007

Five of 200 emblems collected and explained by George Wither in his 1635 Collection of Emblemes, Ancient and Moderne (2003 Kessinger facsimile).

“For, when levitie, or a childish delight, in trifling Objects, hath allowed them to looke on the Pictures; Curiositie may urge them to peepe further, that they might seeke out also their Meanings, in our annexed Illustrations; In which, may lurke some Sentence, or Expression so evidently pertinent to their Estates, Persons, or Affections, as will (at that instant or afterward) make way for those Considerations, which will, at last, wholly change them, or much better them, in their Conversation” (pA2).

“What cannot be by Force attain’d, By Leisure, and Degrees, is gain’d” (p49).

“He, that concealed things will finde, Must looke before him, and behinde” (p138).

“Each Day a Line, small tasks appeares. Yet, much it makes in threescore Yeares” (p158).

“True Vertue, whatfoere betides, In all extreames, unmoov’d abides” (p218).

“The Garland, He alone shall weare, Who, to the Goale, doth persevere” (p258).

Rothko and the Breath of Life

July 11th, 2007

Two Rothkos from Jacob Baal-Teshuva’s Rothko (2003 Taschen edition). “The aim of his life’s work was to express the essence of the universal human drama” (p17). Said Rothko, “‘Any picture which does not provide the environment in which the breath of life can be drawn does not interest me'” (p45).

Violet Stripe, 1956.

“‘Silence is so accurate,’ he said, adding that words would only ‘paralyze’ the viewer’s mind. In one conversation he said, ‘Maybe you have noticed two characteristics exist in my paintings; either the surfaces are expansive and push outward in all directions, or the surfaces contract and rush inward in all directions. Between these two poles you can find everything I want to say'” (p50).

Untitled, 1969.

“On another occasion, he announced that, ‘A painting is not about experience. It is an experience'” (p57).

The Four Elements and Metallic Transmutation

July 9th, 2007

Four illustrations appearing in E. J. Holmyard’s 1957 Alchemy, a historical account of exoteric alchemy.

First, a diagram (p22) of the Greek conception of the four elements — fire, air, water, and earth — in relation to their qualities — wet (fluid, moist), dry, hot, and cold.

Each element is described, unequally, by its two adjacent properties; thus fire is primarily hot and secondarily dry, air wet and hot, water cold and wet, and earth dry and cold. “None of the four elements is unchangeable; they may pass into one another through the medium of that quality which they possess in common; thus fire fire can become air through the medium of heat, air can become water through the medium of fluidity; and so on” (p22).

This system (with earlier roots, and similarly present in other cultures) was conceptualized by Aristotle (384 BC — 322 BC), who “argues that each and every other substance is composed of each and every ‘element’, the difference between one substance and another depending on the proportions in which the elements are present… It follows that any kind of substance can be transformed into any other kind by so treating it that the proportions of its elements are changed to accord with the proportions of the elements in the other substance. This may be done by change of the elements originally existing in the first substance, or by adding some substance consisting of such proportions of the elements that when the substances are mixed or combined the desired final proportions are attained” (p23).

“Here we have the germ of all theories of metallic transmutation and the basic philosophical justification of all the laborious days spent by alchemists over their furnaces” (p23) — a point well-illustrated (plate 18) in Mylius’ 1622 Philosophia Reformata (see also earlier post on Mylius):

The spherical fundaments display the alchemical symbols of the four elements (earth, water, air, fire, from left-to-right), while the flaming flasks atop represent so-supported stages of the Work, blackening, whitening, yellowing, reddening, which color changes describe successive objectives of the various alchemical operations: calcination, sublimation, fusion, crystallization, distillation, and putrefaction, among other processes.

Arab alchemist Jabir ibn Hayyan (a.k.a. Geber, 721 — 815) theorized that all metals were formed in the earth by the union of sulphur (that is, philosophical sulphur, dry and hot) and mercury (also philosophical, cold and wet), and that therefore the art of alchemy is the balancing of these two natures (later, salt made three, the tria prima) to produce other metals (e.g., gold). This was the start of a “chemical marriage” that would influence all of European alchemy during its entire extent, as seen (plate 19), for example, in Barchusen’s Elementa Chemia one thousand years later (1718):

Wherein is shown the opposing principles of sun and moon, drawing near over receding waters, with the symbols for sulphur and mercury in close association — thence, if the alchemist is successful, to finally unite, the fusion of oppositions, of male and female, represented by the philosophical androgyne:

“The Grand Hermetic Androgyne trampling underfoot the four elements of the prima materia. From the Codex Germanicus 598″ (plate 34).

Whose imprint can still be seen today:

A Laurent de Brunhoff adaptation of Raffaello Sanzio‘s Saint Michael and the Dragon from Babar’s Museum of Art, 2003 (p15).

Yeats’ Geometry of the Four Faculties

June 30th, 2007

Ten diagrams from W. B. Yeats’ A Vision (“B” edition, 1937). A Vision details an esoteric geometry and its applications, ambiguously channeled via automatic script and speech by Yeats’ wife, George, then organized and augmented by Yeats himself.

“Life is no series of emanations from divine reason such as the Cabalists imagine, but an irrational bitterness, no orderly descent from level to level, no waterfall but a whirlpool, a gyre” (p40, from Robartes). Indeed, two opposing and interpenetrating gyres form “the fundamental symbol of my instructors” (p68):

“If I call the unshaded cone ‘Discord’ and the other ‘Concord’ and think of each as the bound of a gyre, I see that the gyre of ‘Concord’ diminishes as that of ‘Discord’ increases, and can imagine after that the gyre of ‘Concord’ increasing while that of ‘Discord’ diminishes, and so on, one gyre within the other always” (p68). Here the three-dimensional gyres, or spirals, are represented more easily by cones or triangles.

Yeats labels these “struggling states” (p71) the primary and antithetical tinctures:

The primary tincture, shaded, represents objectivity, Concord, space, the solar, the reasonable, plasticity, passivity; the antithetical tincture, unshaded, represents subjectivity, Discord, time, the lunar, the natural, beauty, unity of being. “Whereas subjectivity tends to separate man from man, objectivity brings us back to the mass where we began” (p72).

“Within these cones move what are called the Four Faculties: Will and Mask, Creative Mind and Body of Fate. Will and Mask are the will and its object, or the Is and the Ought; Creative Mind and Body of Fate are thought and its object, or the Knower and the Known. The first two are lunar or antithetical or natural [subjectivity], the second two solar or primary or natural [objectivity]” (p73).

“These pairs of opposites whirl in contrary directions, Will and Mask from right to left, Creative Mind and Body of Fate like the hands of a clock, from left to right… As Will approaches the utmost expansion of its antithetical cone its drags Creative Mind with it — thought is more and more dominated by will. Then, as though satiated by the extreme expansion of its cone, Will lets Creative Mind dominate, and is dragged by it until Creative Mind weakens once more… The Mask and Body of Fate occupy those positions which are most opposite in character to the positions of Will and Creative Mind. If Will and Create Mind are approaching complete antithetical expansion, Mask and Body of Fate are approaching complete primary expansion, and so on. In the following figure the man is almost completely antithetical in nature” (p74-7).

The vertical lines mark the positions of the Faculties in their respective cones. To represent direction, Yeats indicates expanding Faculties along the bottom of the diagram, and contracting Faculties along the top.

“In the following [man is] almost completely primary” (p77).

“In the following he is midway between primary and antithetical and moving towards antithetical expansion” (p78).

“A particular man is classified according to the place of Will, or choice, in the diagram” (p73).

“I have now only to set a row of numbers upon the sides to possess a classification… of every possible movement of thought and of life, and I have been told to make these numbers correspond to the phases of the moon [see last diagram of previous post]. The moonless night is called Phase 1, and full moon in phase 15. Phase 8 begins the antithetical phases, those where the bright part of the moon is greater than the dark, and Phase 22 begins the primary phases, where the dark part is greater than the bright” (p78-9).

Or, drawn lunarly, the Great Wheel:

For each phase, Yeats derives the character and destiny of a man whose Will is so located, and whose Mask, Creative Mind, and Body of Fate have assumed their complimentary locations and influences. This discussion constitutes the largest topic of A Vision. Here are a few excerpts that reveal such interplay.

Phase 10, The Image-Breaker: “If he live like the opposite phase, conceived as a primary condition — the phase where ambition dies — he lacks all emotional power (False Mask: ‘Inertia’), and gives himself up to rudderless change, reform without a vision of form. He accepts what form (Mask and Image) those about him admire and, on discovering that it is alien, casts it away with brutal violence, to choose some other form as alien. He disturbs his own life, and he disturbs all those who come near him more than does Phase 9, for Phase 9 has no interest in others expect in relation to itself. If, on the other hand, he be true to phase, and use his intellect to liberate from mere race (Body of Fate at Phase 6 where race is codified), and so create some code of personal conduct, which implies always ‘divine right’, he becomes proud, masterful and practical. He cannot wholly escape the influence of his Body of Fate, but he will be subject to its most personal form; instead of gregarious sympathies, to some woman’s tragic love almost certainly…” (p122).

Phase 17, The Daimonic Man: “He is called the Daimonic man because Unity of Being, and consequent expression of Daimonic thought, is now more easy than at any other phase. As contrasted with Phase 13 and Phase 14, where mental images were separated from one another that they might be subject to knowledge, all now flow, change, flutter, cry out, or mix into something else; but without, as at Phase 16, breaking and bruising one another, for Phase 17, the central phase of its triad, is without frenzy. The Will is falling asunder, but without explosion and noise. The separated fragments seek images rather than ideas, and these the intellect, seated in Phase 13, must synthesize in vain, drawing with its compass-point a line that shall but represent the outline of a bursting pod. The being has for its supreme aim, as it had at Phase 16 (and as all subsequent antithetical phases shall have), to hide from itself and others this separation and disorder, and it conceals them under the emotional Image of Phase 3; as Phase 16 concealed its greater violence under that of Phase 2. When true to phase the intellect must turn all its synthetic power to this task. It finds, not the impassioned myth that Phase 16 found, but a Mask of simplicity that is also intensity…” (p141).

Phase 25, The Conditional Man: “Born as it seems to the arrogance of belief, as Phase 24 was born to moral arrogance, the man of the phase must reverse himself, must change from Phase 11 to Phase 25; use the Body of Fate to purify the intellect from the Mask, till this intellect accepts some social order, some condition of life, some organised belief: the convictions of Christendom, perhaps. He must eliminate all that is personal from belief; eliminate the necessity for intellect by the contagion of some common agreement… There may be great eloquence, a mastery of all concrete imagery that is not personal expression, because though as yet there is no sinking into the world but much distinctness, clear identity, there is an overflowing social conscience. No man of any other phase can produce the same instant effect upon great crowds; for codes have passed, the universal conscience takes their place. He should not appeal to a personal interest, should make little use of argument which requires a long train of reasons, or many technical terms, for his power rests in certain simplifying convictions which have grown with his character; he needs intellect for their expression, not for proof, and taken away from these convictions is without emotion and momentum. He has but one overwhelming passion, to make all men good, and this good is something at once concrete and impersonal; and though he has hitherto given it the name of some church, or state, he is ready at any moment to give it a new name, for, unlike Phase 24, he has no pride to nourish upon the past. Moved by all that is impersonal, he becomes powerful as, in a community tired of elaborate meals, that man might become powerful who had the strongest appetite for bread and water…” (p173-4).

Finally, Yeats, speaking of his own time and place in history (for the Great Wheel can describe history as well as individual man — another topic in A Vision): “When the new gyre begins to stir, I am filled with excitement. I think of recent mathematical research… with its objective world intelligible to intellect; I can recognize that the limit itself has become a new dimension, that this ever-hidden thing that makes us fold our hands has begun to press down upon multitudes. Having bruised their hands upon that limit, men, for the first time since the seventeenth century, see the world as an object of contemplation, not as something to be remade, and some few, meeting the limit in their special study, even doubt if there is any common experience, doubt the possibility of science” (p300).

A Vital Quickening of the Imagination

June 28th, 2007

A photograph and two diagrams from Clarence R. Smith’s Earth and Sky: Marvels of Astronomy, 1940, part of the University of Knowledge series, edited by Glenn Frank.

What lies beyond? Courtesy Lick Observatory (p170).

“With the earth beneath his feet and the sky above his head, man lives his brief moment in a world he can see and touch and come to know, but sublime mystery shrouds his coming and his going. His twofold passion is to penetrate the mystery and to perfect the mastery of life” (pVII, Frank’s introduction).

A mural showing comparative dimension of natural objects in miles. Courtesy Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago (pV).

“Man might seem to be reduced to utter insignificance in this limitless cosmic scheme. Thus far science has found no evidence that life as we know it exists anywhere but on this planet. Man is the highest form of that life. He alone has the gift of comprehension. He alone must seek the answers to the eternal questions of Whence, Whither, and Why. We cannot study the earth and the countless stars and suns scattered through space without a vital quickening of the imagination. Life itself takes on a new meaning” (pIX, Frank’s introduction).

(The lunar cycle; prelude to the next post.)

Diagrammatic explanation of the phases of the moon (p246).

Issa’s Floating World

June 13th, 2007

Three cutouts by Kyoko Yanagisawa from Issa-Haiku: A Collection of 17-syllable Poem with Cutout-picture (Fujin-sha, 1996), with depicted haiku of Kobayashi Issa, as translated by Takahiko Sakai.

“I sincerely hope young mothers will inscribe Issa’s haiku on their children’s memory using these playing cards as an intermediary. I believe the haiku in the cards will, without fail, give them heart and soul at the turning points in their life” (p111-2).

“In the grounds of the priestless temple,

The cherry blossoms come out,

With their strength putting forth to the full” (p34).

“Now is the best season to eat buckwheat noodles

On your way to and from Zenkoji Temple in the province of Shinano,

Noted for the moon mirrored in each section of the paddy fields” (p48).

“Wild geese,

Don’t cry;

Life is the same wherever you may go” (p54).

Or, as Lewis Mackenzie translates in The Autumn Wind:

“Wild Geese, hush your cry!

Wherever you go it is the same —

The Floating World!” (p76).

A few more Issa’s, translated by Lucien Stryk in The Dumpling Field:

“Moist spring moon –

raise a finger

and it drips” (p11).

“Sundown —

Under cherry blooms

Men scurry home (p13).”

“Old pillar,

sized by

a spanworm” (p14).

“Dawn — fog

of Mt. Asama spreads

on my table” (p61).

“My thinning hair,

eulalia grass,

rustling together” (p67).

“Bright moon,

welcome to my hut —

such as it is” (p72).

The Scholar Immortal

June 6th, 2007

16th century Chinese painting, split into left and right halves, appearing in Alasdair Clayre’s 1984 The Heart of the Dragon.

Left half: floating immortal. Click for larger version.

Right half: sleeping scholar. Click for larger version.

“In a 16th-century painting illustrating a Daoist poem, a scholar asleep in his thatched cottage dreams he is an immortal, floating over the mountains” (p47).

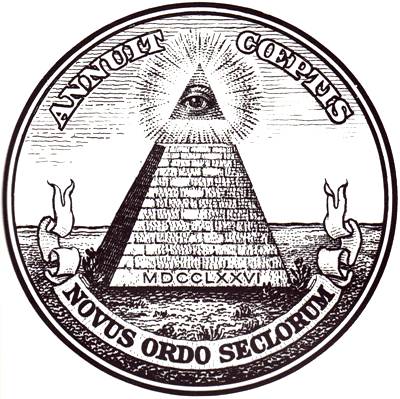

Reverse and obverse of the Great Seal of the United States, engraved on the back of the American dollar bill, with Campbell’s description from The Inner Reaches of Outer Space (see earlier post).

“Whereas behind the pyramid there is only a desert to be seen, before and around it are the sprouting signs of a new and fresh beginning… a ‘new order of the world’ (novus ordo seclorum)” (p126).

“There at the summit of a symbolic pyramid (the World Mountain) we see an eye within a radiant, upward-pointing triangle (the World Eye, God’s Eye, Eye of Spirit). It is at that point of rest (stasis) at the summit where the opposed sides come together” (p125).

“In the radiant disk above the American bald eagle’s head the stars of the original 13 states are composed to form a Solomon’s seal symbolic of the union of soul and body, spirit and matter. Each of the interlaced equilateral triangles, one upward turned, the other downward, is a Pythagorean tetraktys, or ‘perfect triangle of fourness,’ of nine points, four to a side, enclosing a tenth representing the generative center (‘still point of the turning world’) out of which the others derive their force. The upward triangle is of spiritual, the downward pointing, of physical energy. Thus interlaced, the two represent the physical world as informed by the spiritual” (p128).

“When viewed as outlining a pyramid, the upward pointing triangle matches the pyramid on the reverse of the Seal, with the single point at its apex corresponding to the Eye out of which the expanding form of the universe has proceeded. As symbolized in the traditional Pythagorean tetraktys, the energy emanating from that initial point (which is of the opening both from and to Eternity [cf. prajna eye]) yields, first, duality (2 points: measure and chaos, subject and object, light and dark, odd and even, male and female, etc.), which then relate to each other in three ways (3 points: either a dominant, b dominant, or a and b in accord), whence derive all the phenomenal forms in the field of space-time (4 points: 4 quarters of the earth and heavens). There is a verse in the Tao Teh Ching: ‘The Tao produced One; One produced Two; Two produced Three; Three produced All things'” (p128).

“Connotations of the same order pertain, of course, to the downward turned tetraktys, with its single point at the apex opening also from and to Eternity; so that, ‘What is above is below,’ and the energy of the Spirit (however named), whether from without (as from the Eye, the apex above) or from within the world (the apex below) is one” (p128).

Contemplation: the Kuan Hexagram

May 28th, 2007

Hexagram 20, Contemplation, of the I Ching, with King Wen’s explanation from 1143 B.C., as translated by R. G. H. Siu in The Portable Dragon, 1968.

“A person should contemplate the workings of the universe with reverence and introspection. In this way expression is given to the effects of these laws upon his own person. This is the source of a hidden power” (p138).