Alciati’s Emblematum Liber

March 23rd, 2007

Three emblems from Andrea Alciati‘s Emblematum Liber (1549 edition), recently translated by John F. Moffiit.

“The term ’emblema’ was frequently taken by Alciati’s contemporaries to represent the modern equivalent of the ancient hieroglyphs, for these also combined an enigmatic image with a mostly inscrutable text” (Moffit’s introduction, p7). Or, as Alciati’s teacher Filippo Fasanini described them, “short sayings… which can, in combination with painted or sculpted figures, wrap in shrouds the secrets of the mind” (p6). In Emblematum Liber, Alciati encoded 212 such emblems with moralistic allegories, lessons, histories.

Emblem 7 (p23)

NOT FOR YOU, BUT FOR RELIGION

A dim-witted ass was carrying an image of [the goddess] Isis, so bearing upon its bent back the venerated mysteries. Every passerby along its route worshipped the Goddess with reverence, falling to their knees to offer her their pious prayers. The ass, however, assumed that the honors were only being given to himself, and he swelled up with pride. This stopped when the donkey driver, correcting him with some whiplashes, told him: “You are not God, you half-baked ass, but only the bearer of God.”

Emblem 16 (p33)

LIVE SOBERLY AND DO NOT ACCEPT BELIEFS HEEDLESSLY

States Epicharmus: “Never be credulous nor cease to be sober.” These are the sinews and members of the human mind. Behold the hand with an eye upon it; it only believes what it sees. Here is shown the mint, the herb symbolizing ancient sobriety. Brandishing this plant, Heraclitus pacified and soothed the maddened mob bursting into frenzied revolt.

Emblem 182 (p211)

WHATEVER IS MOST ANCIENT IS IMAGINARY

“Old man from Pallenia, oh Proteus, you have as many shapes as an actor has roles. Why are your members sometimes that of a man, and sometimes that of an animal? Come on, tell me, what can be the reason for you to change into all manner of shapes, and yet you have no fixed form of your own?” “I reveal the signs belonging to the most remote ages, ancient and prehistoric, and each man imagines them according to his whimsy.”

Doyle on Fairies

March 15th, 2007

Three photographs of the The Cottingley Fairies, as described in Arthur Conan Doyle‘s The Coming of Fairies (1922), recently reissued by Bison Books. These photographs were taken by two girls (10 and 16 years old) in 1917, and subsequently defended by several as proof of fairies—including Doyle, who was evidently influenced by his interest in the Spiritualism and Theosophy movements.

“The recognition of their existence will jolt the material twentieth-century out of its heavy ruts in the mud, and will make it admit that there is a glamour and a mystery to life” (p58).

“To the objections of photographers that the fairy figures show quite different shadows to those of the human our answer is that ectoplasm, as the etheric protoplasm has been named, has a faint luminosity of its own, which would largely modify shadows” (p53).

Doyle quotes C. W. Leadbeater: elemental fairies (being one type of fairy) “are the thought-forms of the Great Beings, our angels, who are in charge of the evolution of the vegetable kingdom. When one of these Great Ones has a new idea connected with one of the kinds of plants or flowers which are under his charge, he often creates a thought-form for the special purpose of carrying out that idea. It usually takes the form either of an etheric model of the flower itself or of a little creature which hangs round the plant or the flower all through the time that the buds are forming, and gradually builds them into the shape and colour of which the angel has thought. But as soon as the plant has fully grown, or the flower has opened, its work is over and its power is exhausted, and, as I have said, it just simply dissolves, because the will to do that piece of work was the only soul that it had” (p187/8).

Finally, in a 1981 interview (some 60 years later), the girls (then women) admitted they fabricated the fairies by tracing pictures from Princess Mary’s Gift Book (1914).

Itten and Phantasmagorical Resonance

March 9th, 2007

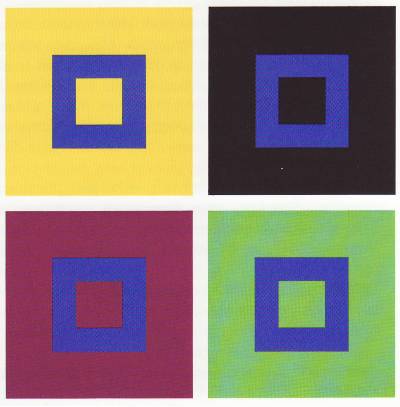

Three figures from Johannes Itten‘s The Elements of Color, 1961.

“Colors of equal brilliance” (p39).

“The doctrine to be developed here is an aesthetic color theory originating in the experience and intuition of a painter. For the artist, effects are decisive, rather than agents as studied by physics and chemistry. Color effects are in the eye of the beholder. Yet the deepest and truest secrets of color effect are, I know, invisible even to the eye, and are beheld by the heart alone. The essential eludes conceptual formulation” (p7).

“Combinations showing how the same blue… [is] altered in expression by different juxtaposed colors” (p87).

“Symbolism without visual accuracy and without emotional force would be mere anemic formalism; visually impressive effect without symbolic verity and emotional power would be banal imitative naturalism; emotional effect without constructive symbolic content or visual strength would be limited to the plane of sentimental expression” (p13).

“Harmonious proportions of areas for complementary colors” (p60).

“Doctrines and theories are best for weaker moments. In moments of strength, problems are solved intuitively, as if of themselves” (p7).

The Etchings of Piranesi

March 3rd, 2007

Three etchings by the antiquarian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720—1778), reprinted in Luigi Ficacci’s Taschen edition.

Remains of the tomb of the Metelli. Click image to view larger version.

“When he can devote himself exclusively to ancient Romain remains, his style fully realizes the visionary originality that… he dedicated to representation of the ancient monuments” (p22).

View of the subterranean foundation of the mausoleum. Click image to view larger version.

“His prints ‘showed’ things in an unprecedented and unimaginable way… [they] revealed a previously unknown aspect and represented a totally unknown world that, notwithstanding the precision of his rendering, was loaded with an extraordinary forceful charge of information” (p8).

Tomb of the three Curatii brothers in Albano. Click image to view larger version.

“Over the course of their formal evolution, a forest of new content appeared — cryptic, symbolic, allegorical and synthesized into an extremely pictorial vision that could simultaneously appear to be a decorative whim or a mine of recondite meanings, while the initial subject, neutral in itself, was transformed into a composition. This was a game of intentional ambiguities that could function differently according to the disposition and critical capacity of the observer himself” (p24/5).

Fe Fi Fo Fum and Apothegmatical Pedantry

February 24th, 2007

Two illustrations reprinted in Iona and Peter Opie’s The Classic Fairy Tales (1974). From a 1794 edition of Tommy Thumb’s Song Book, for all little Masters and Misses (p63), we see the giant’s refrain:

Then, in The History of Tom Thumbe (1621 edition), from the “gyant” while searching for Tom (p40):

Now fi, fee, fau, fan,

I feele smell of a dangerous man:

Be he alive, or be he dead,

Ile grind his bones to make me bread.

Onto Jack the Giant Killer (1761 edition, p63):

Fee, fau, fum,

I smell the blood of an English man,

Be he alive, or be he dead,

I’ll grind his bones to make my bread.

The Opies footnote the pattern as “perhaps the most famous war cry in English literature” (p63), common to British tales of giants and ogres, in numerous versions, such as:

Fe, fi, fo, fum,

I smell the blood of an Englishman;

If he have any liver and lights

I’ll have them for my supper tonight.

But as to its origins? Thomas Nashe cautions in Haue with You to Saffrom-Walden (1596, p48):

O, tis a precious apothegmaticall Pedant, who will finde matter inough to dilate a whole daye of the first inuention of Fy, fa, fum, I smell the bloud of an Englishman.

Which brings to mind this woodcut from an 1840 edition of Jack the Giant Killer (p59):

Still, leaving Opie, a two-part footnote in Jacobs’ English Fairy Tales (p152) tantalizes. First, in the 1889 The Folk-tales of the Magyars, Kriza et al. review cross-cultural olfactory keenness of folk creatures, and include this elf king’s version (p341):

With fi, fe, fa, and fum,

I smell the blood of a Christian man,

Be he dead, be he living, with my brand,

I’ll clash his harns frae his harns pan.

Then, in his introduction to Perrault’s Popular Tales (pCVI/II), Lang traces the blood-scent archetype back to at least Aeschylus’ Eumenides from 458 BC, wherein the Furies trace the scent of Orestes (“The smell of human blood gives me a smiling welcome” (l252))—although their apothegms miss apophony.

Sprague’s Paradise Lost Diagrams

February 17th, 2007

Two diagrams from Homer Sprague‘s 1883 edition of Milton‘s Paradise Lost: the first, Milton’s cosmography; the second, Satan’s “probable course” from hell, through Chaos, to our own world, hanging fast to heaven.

“Such place eternal justice has prepared

For those rebellious; here their prison ordained

In utter darkness, and their portion set

As far removed from God and light of heaven

As from the centre thrice to the utmost pole.

Oh, how unlike the place from whence they fell!” (p16/7).

“Farewell happy fields,

Where joy forever dwells! Hail, horrors! hail,

Infernal world! and thou, profoundest Hell,

Receive thy new possessor! one who brings

A mind not to be changed by place or time.

The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven.

What matter where, if I be still the same…” (p30).

—“So Satan spake” (p31).

Click image to view larger, legible version.

“Long is the way

And hard, that out of hell leads up to light.

Our prison strong, this huge convex of fire,

Outrageous to devour, immures us round

Ninefold; and gates of burning adamant,

Barred over us, prohibit all egress.

These passed, if any pass, the void profound

Of unessential night receives him next,

Wide gaping, and with utter loss of being

Threatens him, plunged into that abortive gulf.

If thence he scape into whatever world

Or unknown region, what remains him less

Than unknown dangers, and as hard escape?” (p77/8).

Gell on Articulatory Landscapes

February 11th, 2007

An illustration from Alfred Gell’s “The Language of the Forest,” reprinted in The Art of Anthropology.

“One can indeed imagine the Umeda world/landscape as a series of articulatory gestures, syllabic shapes moulded within the oral tract (microcosm) and the macrocosm consisting of the body, social relationships mediated through the body, and other natural forms, particularly trees, and the encompassing physical ambiance” (p242).

Click image to view larger, legible version.

“In the New Guinea forest habitat [dense, unbroken jungle]… hearing is relatively dominant (over vision) as the sensory modality for coding the environment as a whole… Umeda, and languages like Umeda, are phonologically iconic, because they evoke a reality which is itself ‘heard’ and imagined in the auditory code, whereas languages like English are non-iconic because they evoke a reality which is ‘seen’ and imagined in the visual code” (p247/8).

“Even vicarious participation in alterity is subversive of the conceptual restrictions which motivate our own sense of the real, and, by derivation, our conceptions of the poetic” (p257).

Freher’s Paradoxical Emblems

February 8th, 2007

Two emblems from Dionysius Andreas Freher’s Paradoxa Emblemata (71 and 76), written in the early 18th century. Through a sequence of 153 such emblems, Freher (born 1649) illustrates Jakob Böehme‘s mystical cosmology: a progression beginning at a natural unity, differentiating via free will—even rebellion, and finally returning to a more sublime unity.

What Thou hast of One yield to that One again, if thou intendest to keep it. Only by doing so canst thou be a perpetuum Mobile.

Although distributed amongst his peers in manuscript form, Paradoxa Emblemata was never published. The emblems here are taken from Adam McLean‘s hand-bound edition, produced in 1983, and based on manuscript 5789 in the British Library.

From whence is this & that, if not out of the Center?

“When one… begins to use these [emblems] in meditation, as opposed to merely intellectualising over them, one will find that it is difficult to exhaust the implications of each emblem. …The meditator will find the sequence to slowly unfold its beauty of construction and see how each step builds upon the former… to… sense the inner architecture of the emblems…” (McLean introduction, p6).

Yantras in Tantra Art

February 3rd, 2007

Two yantras from Rajasthan in Tantra Art by Ajit Mookerjee (1971 edition, plates 43 and 45).

“The dynamic graph of the diagram of forces by which anything can be represented—the picture of its functional constitution—is called the yantra of that thing. It is not an arbitrary invention but a revealed image of an aspect of cosmic structure” (p20).

The yantra below “tries to express primordial vibrations, or spandas, the ‘cosmic drum of sound’, which by their lines of sound-energy create a dual ‘magnetic field’. Here vibrations are slowed down at laya (absorption) points” (p80).

“And just as the musical string must be plucked in a particular fashion to sound a certain note, so must the yantra line be mastered and mentally plucked to bring forth its image or power” (p21).