The Face of a Person

October 22nd, 2008

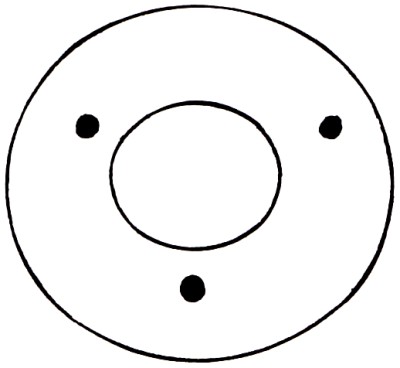

Speaking of eyes and wings, a talismanic scroll presented in Mercier’s 1979 Ethiopian Magic Scrolls.

“The central design, a face within an eight-pointed star, is the most common and most characteristic motif in Ethiopian scrolls. The face is known as gätsä säb’e (‘face of a person’). It is the face connected with the prayer that goes with the talisman, and its presence is necessary for the effectiveness of the scroll. Thus defined, the face has a sort of ‘local’ identity. A generic meaning can also be attributed to it, interpretable with help of the accompanying prayer: the face of God, an angel, a demon, a man, and so on.

“The eight points indicate the four directions of the talisman’s protective power: ‘Whoever comes from the East, etc…’. In relation to the face in the center, they are luminous radiance or the wings that enable it to move in all directions. One dabtara has said that each of the eight wings is an angel serving the central face. He is referring implicitly to a passage from the Apocrypha of Clement (or Qälémentos): ‘The family of angels is numerous. They have no single aspect. Indeed, there are some who have many eyes; some who are only eyes; some who are a burst of light brighter than the light of the sun; some who have faces like a man’s face; some who have two wings; some who have one wing; some who are two wings; some who are all one wing’. Therefore, in a picture like this, eyes, face, and wings can all be angels” (p9).

Franck and the Quality of Awareness

October 20th, 2008

A drawing by Frederick Franck from his 1973 The Zen of Seeing.

“The purpose of ‘looking’ is to survive, to cope, to manipulate, to discern what is useful, agreeable, or threatening to the Me, what enhances or what diminishes the Me…

“When, on the other hand, I SEE — suddenly I am all eyes, I forget this Me, am liberated from it and dive into the reality of what confronts me, become part of it, participate in it…

“It is in order to really SEE, to SEE ever deeper, ever more intensely, hence to be fully aware and alive, that I draw what the Chinese call ‘The Ten Thousand Things’ around me. Drawing is the discipline by which I constantly rediscover the world” (p5-6).

“Zen raises the ordinariness of The Ten Thousand Things to sacredness and it debunks much that we consider sacrosanct as being ordinary. What we consider supernatural becomes natural, while that which we have always seen as so natural reveals how wondrously supernatural it is” (p112).

“Where there is revelation, explanation becomes superfluous. Curiosity is dissolved in wonder” (p28).

“SEEING/DRAWING is, beyond words and beyond silence, the artist’s response to being alive. Insofar as it has anything to transmit, it transmits a quality of awareness” (p120).

Szukalski and the Eyes of Inspiration

September 12th, 2008

A 1966 drawing by Szukalski of a never-done monument, reproduced in Struggle: The Art of Szukalski (also see previous posts).

Monument to Jules Stein Eye Institute, 1966. Click for larger version.

“Ever since the eye hospital was built in Westwood, California, I have wished to make a monument to its donor, Jules Stein. Not knowing his face, I placed the portrait of a stranger in its place in my drawing of the project.

“He is eagerly stepping forward from his prayerful kneeling position to magically touch the blind child’s eyes so that it may see. To see his wonderful world will be the most glorious of it’s experiences, for, like any child, it is but a foreigner…

“Please note the peacock feathers that make up the pedestal to this monument. It has two kinds of eyes; the ones that see and the ones that have no eyeballs. Instead of Wings of Inspiration, I gave the donor of this superb hospital the Eyes of Inspiration” (p109).

On the eye-wings is an inscription that reads:

To see,

To perceive,

To foresee,

To conceive,

So to create

More light.

Enard and the Quality of Attention

August 23rd, 2008

A painting by André Enard appearing in An Art of Our Own by Roger Lipsey.

Number 27, 1975, oil and goldleaf on wood (black-and-white reproduction).

“What are we looking at? A geometry that recalls both the Platonic ‘perfect figures’ and Tantric designs, the image of the labyrinth rendered as a looping intestinal pattern, gestational images of seed and egg — drawn into a whole by craftsmanship that brings to mind the skills of jeweler and icon-maker” (Lipsey, p414).

Enard writes, in a 1987 letter to the author, “Most manifestations of art today lack good common sense, lack relation with a higher reality, and lack spiritual purpose.

“What can there be of value without a search into oneself, linked to essential knowledge?

“Isn’t the ultimate desire of human beings to perceive an order of laws that surpasses us yet is also within us, and to participate in that order?

“Isn’t the role of the artist to reflect on and to reflect back something of this greater order, for the sake of stimulating the viewer to reconstruct the original idea?

“Isn’t this quest the purpose, conscious or unconscious, of all artistic effort?

“To try to grasp the soul, that which animates each thing at its source!

“Finally, what seems most important in the process of painting is the quality of feeling that the artist conveys by doing what he does, no matter what subject he chooses; and then, the care he takes and the quality of attention he communicates, which may arouse the same quality in the viewer.

“When that quality of energy is there, it can be felt — it is palpable, visible in the canvas. It has an action; one is touched, and one can glimpse the reality behind appearances.

“The act of painting can be understood as an act of contemplation, of meditation, through which the artist can rediscover and remember what is laid down in his deepest nature, his primal consciousness — and by that very means summon the same in response from the viewer” (p415-6).

Tantra Art as Psychic Matrix

August 16th, 2008

Four images from Mookerjee’s The Tantric Way (see also these yantras).

“Tantra is a creative mystery which impels us to transmute our actions more and more into inner awareness: not by ceasing to act but by transforming our acts into creative evolution. Tantra provides a synthesis between spirit and matter to enable man to achieve his fullest spiritual and material potential. Renunciation, detachment and asceticism — by which one may free oneself from the bondage of existence and thereby recall one’s original identity with the source of the universe — are not the way of tantra. Indeed, tantra is the opposite: not a withdrawal from life, but the fullest possible acceptance of our desires, feelings, and situations as human beings.

“Tantra has healed the dichotomy that exists between the physical world and its inner reality, for the spiritual, to a tantrika, is not in conflict with the organic but rather its fulfillment. His aim is not the discovery of the unknown but the realization of the known, for ‘What is here, is everywhere. What is not here, is nowhere’ (Visvasara Tantra); the result is an experience which is even more real than the experience of the objective world” (p9).

Gunas: sattva, rajas, tamas (p95).

Tantra art “is specially intended to convey a knowledge evoking a higher level of perception, and taps dormant sources of our awareness. This form of expression is not pursued like detached speculation to achieve aesthetic delight, but has a deeper meaning. Apart from aesthetic value, its real significance lies in its content, the meaning it conveys, the philosophy of life it unravels, the world-view it represents. In this sense tantra art is visual metaphysics” (p41).

Shyama (Kali) Yantra. Rajasthan, 18th century (p35).

Yantra “represents an energy pattern whose force increases in proportion to the abstraction and precision of the diagram. Through these power-diagrams creation and control of ideas are said to be possible” (p34).

The Principle of Fire. Rajasthan, 18th century (p189).

“Tantric images have a meditative resilience expressed mostly in abstract signs and symbols. Vision and contemplation serve as a basis for the creation of free abstract structures surpassing schematic intention. A geometrical configuration such as a triangle representing Prakriti or female energy, for example, is neither a reproduced image nor a confused blur of distortion but a primal root-form representing the governing principle of life in abstract imagery as a sign” (p44).

Salagram, a cosmic spheroid (p13).

Raza’s Prakriti

July 6th, 2008

A painting by S. H. Raza, reproduced in Michel Imbert’s Raza: An Introduction to his Painting.

Prakriti, 1999. Click for larger version.

“This canvas, composed of twenty-five squares, contains in each of them an image suggesting the essence of the elements present in nature [i.e., prakriti]… The following is a schematic explanation of the canvas” (p63):

Row 1: The Sun / Surge of Energy / Sunfilled Sky / The 5 Elements / Polarity

Row 2: The 5 Elements / Nature / Tree with Blue Fruits / Woman’s Buttocks / The Sea

Row 3: Meeting of Male & Female Energies / Male + Female Elements / Bindu of Five Elements / Female Elements / Hill, Tree and Sea

Row 4: The Encounter / Male + Female Elements / Female Sex with 2 Bindus / Female Elements / Title of Canvas in Hindi: Female Element

Row 5: The Space / Male/Female Polarity / The Earth / Male Element (Linga standing) / The Time

Raza on his perception of nature:

“Forms emerge from darkness. Their presence is perceptible in obscurity. They become relevant if their energy is oriented through vision into an alive form-orchestration for which certain prerequisites are indispensable.

“The process is akin to germination. The obscure black space is charged with latent forces asking for fulfillment. Like the universal natural order of the ‘earth-seed’ relationship, the original unit, ‘Bindu’, emerges and unfolds itself in the black space. All inherent forces unite. A vertical line intersects a horizontal line, engendering energy and light. Space is charged. Contours appear: white, yellow, red and blue, and along with the original black, they compose the colour spectrum of the visible world.

“The mysteries of form reveal themselves through light colour space perceptions. In a visible energy spectacle, certain fundamental elements are intricately interrelated and determine the nature of form. Their understanding is indispensable in any creative process. Whatever the direction art expression may take, the language of form imposes its own inner logic and reveals infinite variations and mutations. The mind can only partially perceive these mysteries. The highest perception is of an intuitive order, where all human faculties participate, including the intelligence, that is ultimately a minor participant in the creative process. This stage is total bliss and defies analysis” (p66/8).

The Pneumo-Cosmic Manuscript

June 16th, 2008

Five paintings from the Pneumo-Cosmic Manuscript, an enigmatic sequence of 52 such alchemical illustrations. Neither the author nor the date of the work are known (although the paper establishes a terminus a quo of mid to late 18th century), and no explanatory text is provided beyond a brief introductory paragraph (see below). The present edition was reproduced from a manuscript in Glasgow University’s Ferguson collection and hand-bound by Adam McLean.

“A work of natural magic, fashioned with an admirable brush of pneumo-cosmic nature. The characteristics of the universal prototype of Chaos, through the artful ape of Nature, have been represented to itself in many images, and preserved to eternity the memory of this matter” (title page, from the Latin).

V.

XX.

XXV.

XLIX.

XLVII.

So Bleats the Nuclear Platypus

May 22nd, 2008

Three images from the second edition (2008) of the Nuclear Platypus Biscuit Bible by Pope Gus (see previous post for first edition imagery).

The God-Biscuit (p102).

The new edition sports expanded cantos, several new appendices, and satisfyingly addresses a number of long-standing erratum. In the latter camp, for example, the humanoid used-car salesman facade of Xe8eX’s Presidential disguise is properly named Shaquille O’Neal (p23); and the strange species of creature post-dating the dinosaurs is correctly designated hornulus (p60), rather than dorkosaurus, reflecting recent evidence that these critters were more horny than dorky.

And Pope Gus finally makes good on the foreshadowing in the Gospel of Quxxxzxxx in which it states of the Oozumgreep, “What it would be we could not yet tell, but whatever it was involved propellers and an unconscionable amount of rayon” (p52). As we now know, these are the creatures that, thousands of years later, would propel[ler] the BisQuitus-era UFOs that ferried “I” away from the end times. (For bonus points, compare and contrast the updated UFO manifest.)

Only a careful reading, however, reveals the subtle revisions that evidence the confidence and vision of Pope Gus’s spiritual progress over the nearly two decade hiatus between editions. Perhaps none more so than his reshuffling of the six billion year old Twelve Commandments of the God Biscuit.

Consider, in particular, the original seventh commandment, “I exist only to amuse myself,” and the now tenth commandment, “I and thou exist only to amuse Myself” — an explicit nod to the esoteric teachings of the God Biscuit (“As above, so below”) that remain hidden to the mass of mainstream Arglebargleists. The three-step delta is a clue so formidable I will not call attention to it.

Percipient numerologists will also observe the updated icon of the Nuclear Platypus Himself. For where His Gesture was before a four-sided, four-dimensional “quadrilateral tesseract”, obviously representing the visible Work, the new Gesture goes one hermetic step further, symbolizing the five-sided objective of Perfected Man: “The Platypus most Nuclear had in His right hand something that was neither a noun nor a verb, and in His left hand He gently caressed an aperiodic pentagonal tessellation” (p102).

Sasquatchi hierogyphics (p77).

By now you should have a sense of the significance of this second edition. Therefore, let us rather turn our gaze obversely, to this bonus image, lifted from an Arglebargle brochure, recovered from the Unurthed Vault, so archived there circa 1991:

Morris Louis and Negation

May 17th, 2008

Three paintings by Morris Louis, reproduced with commentary in Morris Louis Now.

Beth Chaf, 1959, cat. 10.

“Lucy Lippard wrote in 1965 that Louis was a ‘meditative action painter,’ and there is something in that oxymoronic phrase — a thoughtful, deliberate expressionist — that captures this view of Louis as the painter of disinterested displays of emotion: feeling, yes, but always subject to elaborate rules” (p22).

Dalet Tet, 1959, cat. 11.

Says Louis, “Am distrustful of over simplifications but nonetheless think that there is nothing very new in any period of art: what is true is that it is only something new for the painter & that this thin edge is what matters. I suspect it is possible to relate every bit of abs. exp. to other art in a breakdown. It comes out new & different when art history is submerged and making a painting is a simple experience not precisely like any the artist had before… I don’t care a great deal for positive accomplishments… that leads to an end… I look at paintings from the negative side, what is left out is useful only as that leads to the next try and the next” (p45).

Alpha Tau, 1960-61, cat. 21, click for larger version.

“To use one of Fried’s favorite words, the only ‘perspicacious’ thing about [Louis’s Unfurleds] is their slight of hand: perception is made oddly criminal, perverse, or underhanded because it is pushed to grasp color quickly on the margins. One looks at these huge works in complete bafflement. I am tempted to say that negation is not experienced here but read. But this is not the case. Faced with the overwhelming presence of negation, front and center, it is color that is read or that does the narrating. Confronted by the monumental chiasm of Alpha Tau, for example, it is as if one can steal only furtive glances of the ribbons that are spread or pushed to the sides. Looking directly at these ribbons renders them devoid of meaning or sense: they exist as inconsequential details in comparison with the expanse of blank canvas. One feels insincere or disingenuous to the painter’s intention when one does focus on the ribbons. One knows that in focusing on either end one is blinding oneself to the position that color occupies within the whole. Color is best served here when buried in a uniquely metonymic grave, not only within and beyond negation but distinctly beside or just past it” (p53).

Color as Field

April 12th, 2008

Four paintings from the Color as Field exhibition currently at the American Art Museum, with notes from the associated catalogue by Karen Wilkin.

Jules Olitski, Tin Lizzie Green, 1964, plate 24.

“While scrupulously avoiding anything resembling psychological symbolism, the ‘post-painterly’ conception of ‘cool’ included the belief that a painting, no matter how apparently restrained, could address the viewer’s whole being — emotions, intellect, and all — through the eye” (p17).

Friedel Dzubas, Lotus, 1962, plate 32.

“Discrete shapes, dynamic imbalances, cursive drawing, and even the most elliptical, implicit suggestions of narrative were all jettisoned, in various combinations and sometimes all at once. The single indispensable element proved to be color — in generous amounts — which, paradoxically, both emphasized the painting’s presence as an object and suggested vast, ambiguous spaces that one saw into but could not, even metaphorically, enter” (p17, 22).

Morris Louis, Mem, 1959, plate 16.

“This emphasis on color was usually allied with a strenuous avoidance of the materiality so crucial to gestural Abstract Expressionism. Touch could be so reduced that paint applications in Color Field abstractions can seem, depending on our sympathies, either inexplicably magical or almost mechanical. Color can appear to have been breathed onto the surface or, when thinned down and soaked into the canvas, to have fused with it, the way dye fuses with fabric. The results is an ineffable, seemingly weightless expanse. Even though essentially all we are left to contemplate are the physical materials of painting (refined as they are), the result is an exquisitely rarefied type of abstraction in which material means are almost completely subservient to the visual. Any lingering vestiges of the painting’s lost history as depiction disappear, and we are faced with pure, eloquent, wordless seeing” (p22).

Kenneth Noland, Earthen Bound, 1960, plate 19.