So Bleats the Nuclear Platypus

May 22nd, 2008

Three images from the second edition (2008) of the Nuclear Platypus Biscuit Bible by Pope Gus (see previous post for first edition imagery).

The God-Biscuit (p102).

The new edition sports expanded cantos, several new appendices, and satisfyingly addresses a number of long-standing erratum. In the latter camp, for example, the humanoid used-car salesman facade of Xe8eX’s Presidential disguise is properly named Shaquille O’Neal (p23); and the strange species of creature post-dating the dinosaurs is correctly designated hornulus (p60), rather than dorkosaurus, reflecting recent evidence that these critters were more horny than dorky.

And Pope Gus finally makes good on the foreshadowing in the Gospel of Quxxxzxxx in which it states of the Oozumgreep, “What it would be we could not yet tell, but whatever it was involved propellers and an unconscionable amount of rayon” (p52). As we now know, these are the creatures that, thousands of years later, would propel[ler] the BisQuitus-era UFOs that ferried “I” away from the end times. (For bonus points, compare and contrast the updated UFO manifest.)

Only a careful reading, however, reveals the subtle revisions that evidence the confidence and vision of Pope Gus’s spiritual progress over the nearly two decade hiatus between editions. Perhaps none more so than his reshuffling of the six billion year old Twelve Commandments of the God Biscuit.

Consider, in particular, the original seventh commandment, “I exist only to amuse myself,” and the now tenth commandment, “I and thou exist only to amuse Myself” — an explicit nod to the esoteric teachings of the God Biscuit (“As above, so below”) that remain hidden to the mass of mainstream Arglebargleists. The three-step delta is a clue so formidable I will not call attention to it.

Percipient numerologists will also observe the updated icon of the Nuclear Platypus Himself. For where His Gesture was before a four-sided, four-dimensional “quadrilateral tesseract”, obviously representing the visible Work, the new Gesture goes one hermetic step further, symbolizing the five-sided objective of Perfected Man: “The Platypus most Nuclear had in His right hand something that was neither a noun nor a verb, and in His left hand He gently caressed an aperiodic pentagonal tessellation” (p102).

Sasquatchi hierogyphics (p77).

By now you should have a sense of the significance of this second edition. Therefore, let us rather turn our gaze obversely, to this bonus image, lifted from an Arglebargle brochure, recovered from the Unurthed Vault, so archived there circa 1991:

Morris Louis and Negation

May 17th, 2008

Three paintings by Morris Louis, reproduced with commentary in Morris Louis Now.

Beth Chaf, 1959, cat. 10.

“Lucy Lippard wrote in 1965 that Louis was a ‘meditative action painter,’ and there is something in that oxymoronic phrase — a thoughtful, deliberate expressionist — that captures this view of Louis as the painter of disinterested displays of emotion: feeling, yes, but always subject to elaborate rules” (p22).

Dalet Tet, 1959, cat. 11.

Says Louis, “Am distrustful of over simplifications but nonetheless think that there is nothing very new in any period of art: what is true is that it is only something new for the painter & that this thin edge is what matters. I suspect it is possible to relate every bit of abs. exp. to other art in a breakdown. It comes out new & different when art history is submerged and making a painting is a simple experience not precisely like any the artist had before… I don’t care a great deal for positive accomplishments… that leads to an end… I look at paintings from the negative side, what is left out is useful only as that leads to the next try and the next” (p45).

Alpha Tau, 1960-61, cat. 21, click for larger version.

“To use one of Fried’s favorite words, the only ‘perspicacious’ thing about [Louis’s Unfurleds] is their slight of hand: perception is made oddly criminal, perverse, or underhanded because it is pushed to grasp color quickly on the margins. One looks at these huge works in complete bafflement. I am tempted to say that negation is not experienced here but read. But this is not the case. Faced with the overwhelming presence of negation, front and center, it is color that is read or that does the narrating. Confronted by the monumental chiasm of Alpha Tau, for example, it is as if one can steal only furtive glances of the ribbons that are spread or pushed to the sides. Looking directly at these ribbons renders them devoid of meaning or sense: they exist as inconsequential details in comparison with the expanse of blank canvas. One feels insincere or disingenuous to the painter’s intention when one does focus on the ribbons. One knows that in focusing on either end one is blinding oneself to the position that color occupies within the whole. Color is best served here when buried in a uniquely metonymic grave, not only within and beyond negation but distinctly beside or just past it” (p53).

Connection in Taijiquan

April 16th, 2008

A diagram from Kuo Lien-Ying’s T’ai Chi Boxing Chronicle. The diagram connects several of taijiquan‘s significant energies, or jins, representing the nature of each jin with an expressive curve.

For example, the serpentine curve between Open and Close represents Folding: “Folding transitions are connected without interruption. Folding is done with the hands, revolving is done with the legs. Folding brings the opponent’s movements to the extremity; thus you fold when you receive. It lengthens energy and is never intermittent or broken off.

“If you intend to move upward, then first fold from below. If you intend to move to the left, then the folding must start from the right. This way the energies are mutually connected. Also, a firm grasp of this drawing of silk exists, so one never receives straight, directly, or rigidly. This contains the idea of the hands working together in accordance with the steps. Regardless of whether you enter forward or retreat backward, the steps must follow the turning of the body to the left or right. Never enter straight or retreat rigidly. The energy inside the legs is stable and sinks without being intermittent or broken off. Boxing chronicles say that the forward and returning motions must have folding; enter and retreat must have revolving” (p103).

Color as Field

April 12th, 2008

Four paintings from the Color as Field exhibition currently at the American Art Museum, with notes from the associated catalogue by Karen Wilkin.

Jules Olitski, Tin Lizzie Green, 1964, plate 24.

“While scrupulously avoiding anything resembling psychological symbolism, the ‘post-painterly’ conception of ‘cool’ included the belief that a painting, no matter how apparently restrained, could address the viewer’s whole being — emotions, intellect, and all — through the eye” (p17).

Friedel Dzubas, Lotus, 1962, plate 32.

“Discrete shapes, dynamic imbalances, cursive drawing, and even the most elliptical, implicit suggestions of narrative were all jettisoned, in various combinations and sometimes all at once. The single indispensable element proved to be color — in generous amounts — which, paradoxically, both emphasized the painting’s presence as an object and suggested vast, ambiguous spaces that one saw into but could not, even metaphorically, enter” (p17, 22).

Morris Louis, Mem, 1959, plate 16.

“This emphasis on color was usually allied with a strenuous avoidance of the materiality so crucial to gestural Abstract Expressionism. Touch could be so reduced that paint applications in Color Field abstractions can seem, depending on our sympathies, either inexplicably magical or almost mechanical. Color can appear to have been breathed onto the surface or, when thinned down and soaked into the canvas, to have fused with it, the way dye fuses with fabric. The results is an ineffable, seemingly weightless expanse. Even though essentially all we are left to contemplate are the physical materials of painting (refined as they are), the result is an exquisitely rarefied type of abstraction in which material means are almost completely subservient to the visual. Any lingering vestiges of the painting’s lost history as depiction disappear, and we are faced with pure, eloquent, wordless seeing” (p22).

Kenneth Noland, Earthen Bound, 1960, plate 19.

Florensky on Gold

March 19th, 2008

Three more icons (see previous post), and Florensky (again, from Iconostasis) on the use of gold-leaf in iconpainting.

![]()

The Holy Face (The Vernicle) icon, 16th century.

“The whole of iconpainting seeks to prove — with an ultimate persuasiveness — that the gold and the paint are wholly incommensurable. The happiest icon attains this, for in its gold we can discern not the slightest dullness or darkness or materiality. The gold is pure, ‘admixtureless’ light, a light impossible to put on the same plane with paint — for paint, as we plainly see, reflects the light: thus, the paint and the gold, visually apprehended, belong to wholly different sphere of existence. Gold is therefore not a color but a tone” (p123).

“Depicting this unmingling mingling is the representation of the invisible dimension of the visible, the invisible understood now in the highest and ultimate meaning of the word as the divine energy that penetrates into the visible so that we can see it” (p127).

![]()

Archangel Michael icon, 14th century.

“In the iconpainting process, the golden color of superqualitative existence first surrounds the areas that will become the figures, manifesting them as possibilities to be transfigured so that the abstract non-existents become concrete non-existents; i.e., through the gold, the figures become potentialities. These potentialities are no longer abstract, but they do not yet have distinct qualities, although each of them is a possibility of not any but of some concrete quality. The non-existent has become the potential. Technically speaking, the operation is one of filling in with color the spaces defined by the golden contours so that the abstract white silhouette becomes the concrete colorful silhouette of the figure — more precisely, it begins to become the concrete colorful silhouette of the figure. For at this point, the space does not yet posses true color; rather, it is only not a darkness, not wholly a darkness, having now the first gleam of light, the first shimmer of existence out from the dark nothingness. This is the first manifestation of the quality, color, a little bit illumined by light… Reality is revealed by the degrees of the manifestation of existence” (p138).

![]()

St. John the Baptist icon, 15th century.

“I call your attention to this remarkable sentence: the icon is executed upon light — a sentence perfectly expressing the whole ontology of iconpainting. When it corresponds most closely to iconic tradition, light shines golden, i.e., it is pure light and not color. In other words, every iconic image appears always in a sea of golden grace, ceaselessly awash in the waves of divine light. In the heart of this light ‘we live, and move, and have our being’; it is the space of true reality. Thus, we can comprehend why golden light is the icon’s true measure: any color would drag the icon to earth and weaken its whole vision” (p136-7).

Florensky’s Iconostasis

March 15th, 2008

Three Orthodox icons, the painting of which is described in Pavel Florensky‘s Iconostasis. Thanks go to Polymathicus for recommending this essential text.

![]()

Archangel Gabriel icon, 16th century.

“In creating a work of art, the psyche or soul of the artist ascends from the earthly realm into the heavenly; there, free of all images, the soul is fed in contemplation by the essences of the highest realm, knowing the permanent noumena of things; then, satiated with this knowing, it descends again to the earthly realm. And precisely at the boundary between the two worlds, the soul’s spiritual knowledge assumes the shapes of symbolic imagery: and it is these images that make permanent the work of art. Art is thus the materialized dream, separated from the ordinary consciousness of waking life.

“In this separation, there are two moments that yield, in the artwork, two types of imagery: the moment of ascent into the heavenly realm, and the moment of descent into the earthly world. At the crossing of the boundary into the upper world, the soul sheds — like outworn clothes — the images of our everyday emptiness, the psychic effluvia that cannot find a place above, those elements of our being that are not spiritually grounded. At the point of descent and re-entry, on the other hand, the images are experiences of mystical life crystallized out on the boundary of two worlds. Thus, an artist misunderstands (and so causes us to misunderstand) when he puts into his art those images that come to him during the uprushing of his inspiration — if, that is, it is only the imagery of the soul’s ascent. We need, instead, his early morning dreams, those dreams that carry the coolness of the eternal azure. The other imagery is merely psychic raw material, no matter how powerfully it affects him (and us), no matter how artistically and tastefully developed in the artwork. Once we understand this difference, we can easily distinguish the ‘moment’ of an artistic image: the descending image, even if incoherently motivated in the work, is nevertheless abundantly teleological; hence, it is a crystal of time in an imaginal space. The image of ascent, on the other hand, even if bursting with artistic coherence, is merely a mechanism constructed in accordance with the moment of its psychic genesis. When we pass from ordinary reality into the imagined space, naturalism generates imaginary portrayals whose similarity to everyday life creates an empty image of the real. The opposite art — symbolism — born of the descent, incarnates in real images the experience of the highest realm; hence, this imagery — which is symbolic imagery — attains a super-reality” (p44-5).

![]()

Black Madonna of Czestochowa icon, 14th century.

“Icons, as St. Dionysus Aeropagite says, are ‘visible images of mysterious and supernatural visions.’ An icon is therefore always either more than itself in becoming for us an image of a heavenly vision or less than itself in failing to open our consciousness to the world beyond our senses — then it is merely a board with some paint on it. Thus, the contemporary view that sees iconpainting as an ancient fine art is profoundly false. It is false, first of all, because the very assumption that a fine art possesses its own intrinsic power is, in itself, false: a fine art is either greater or less than itself. Any instance of fine art (such as a painting) reaches its goal when it carries the viewer beyond the limitations of empirically seen colors on canvas and into a specific reality, for a painting shares with all symbolic work the basic ontological characteristic of seeking to be that which it symbolizes. But if a painter fails to attain this end, either for a specific group of viewers or for the world in general, so that his painting leads no one beyond itself, then his work unquestionably fails to be art; we then call it mere daubs of paint, and so on. Now, an icon reaches its goal when it leads our consciousness out into the spiritual realm where we behold ‘mysterious and supernatural visions.’ If this goal is not reached — if neither the steadily empathic gaze nor the swiftly intuitive glance evokes in the viewer the reality of the other world (as the pungent scent of seaweed in the air evokes in us the still faraway ocean), then nothing can be said of that icon except that it has failed to enter into the works of spiritual culture and that its value is therefore either merely material or (at best) archaeological” (p65-6).

![]()

Prophet Elijah icon, 15th century.

“Both metaphysics and iconpainting are grounded on the same rational fact (or factual rationality) concerning a spiritual appearance: which is that, in anything sensuously given, the senses wholly penetrate it in such a way that the thing has nothing abstract in it but is entirely incarnated sense and comprehended visuality. A Christian metaphysician will therefore never lose concreteness and so, for him, an icon is always sensuously given; equally, the iconpainter can never employ a visual technique that has no metaphysical sensuousness. But the fact that the Christian philosopher consciously compares iconpainting and ontology does not lead the iconpainter to use the philosopher’s terms; rather, the iconpainter expresses Christian ontology not through a study of its teachings but by philosophizing with his brush. It is no accident that the supreme masters of iconpainting were, in the ancient texts, called philosophers; for, although they did not write a single abstract word, these masters (illumined by divine vision) testified to the incarnate Word with their hands and fingers, philosophizing truly through their colors” (p152).

Stolcius on the Stone

March 2nd, 2008

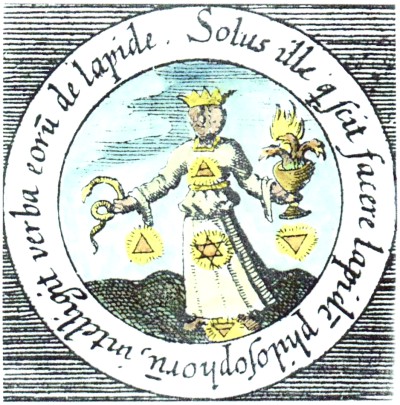

Four emblems from The Hermetic Garden of Daniel Stolcius. This 1620 collection includes 160 emblems appearing in Mylius‘s Opus Medico Chymicum, each accompanied by a four line Latin verse composed by Stolcius. The present edition was hand-colored and -made by Adam McLean.

The selection of emblems below concerns the Philosophical Stone.

Emblem 27: Mitigo, the Philosopher.

However men and beasts despise the Stone, yet it is loved by the wise.

However men and beasts trample the Stone,

It still takes no notice of them all.

For only at the hands of philosophers is it investigated;

These it loves and delights in them especially.

Emblem 62: Author of the Philosophical Rhymes.

You shall visit the interior of the Earth.

He who seeks the Stone shall search the interior of the Earth.

And there shall find where the Medicine lies hidden,

There recognize the many headed Dragon,

There see what may become the Lion by our Art.

Emblem 100: Petrus, Monk and Philosopher.

The fiery little light lives in the Earth, and water cannot extinguish it, for it is heavenly.

This heavenly radiance is hidden in caverns in the ground.

Yet still the moist wave cannot put it out.

Seek it. Revolve the whole world, like Atlas, in your mind.

Perhaps you will find it.

Emblem 107: Hortulanus, Philosopher and Chemist.

Only he who knows how to make the Philosopher’s Stone, understands what they say concerning the Stone.

Only he who knows how to produce our Stone,

Hears the mystic words of the hidden chorus.

Then, in the amazing, different cycle of the Elements, he perceives,

And obtains by entreaty, the longed for riches of Hermogenes.

Solaris by Bertrandt

February 24th, 2008

Andrzej Bertrandt’s 1972 Polish movie poster for Tarkovsky‘s adaptation of Lem‘s Solaris.

Click for full version. From Nostalghia‘s complete collection of Solaris movie posters.

Dali’s 45th Secret

February 16th, 2008

Four drawings by Salvador Dali from his 1948 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship.

Isocahedron, p109.

“Know at once that among the most inexplicable secrets of nature and of creation is that which rules that the number of five governs the animal and vegetable world, that is to say, the organic world, but that on the other hand never, never does this number of five occur in the mineral or inorganic world. So that if the pentagon must become for you the archetypal figure, since in your painting you must express without discontinuity only the quintessence of the organic, the hexagon on the contrary must be considered by you the prototype of your antitype, as well as all its derived crystallizations which are the inorganic ones of the mineral realm.

“You have thus just understood, in learning this, the profound reason of what your painter’s intuition had so surely revealed to you when you confessed to me that you had always detested without knowing why the decorative charm of crystallizations, and especially the congealed, blind, additioned and arithmetical ones of snow. If you do not like them, and are so right in not liking them, it is because your art of painting is exactly the contrary of decorative art, since it is — as you now know — a cognitive art” (p168-9).

Sea urchin, p174.

“I shall… enlighten you without wasting a moment as to Secret Number 45, which concerns the aesthetic virtues of… the sea urchin, in which all the magic splendors and virtues of pentagonal geometry are found resolved, a creature weighted with royal gravity and which does not even need a crown for, being a drop held in perfect balance by the surface tension of its liquid, it is world, cupola and crown at one and the same time, hence universe!

“Bow your head, now, toward the depths of those other celestial abysses of the white calms of the Mediterranean Sea and pull out a sea urchin and accustom yourself to considering the entire universe through the geometric quintessence of its teeth, which form a kind of cosmogonic and pentagonal flower in its lower orifice where is lodged its chewing apparatus, called ‘Aristotle’s lantern’… Painter, take my advice: keep even beside your easel or somewhere close to your work a sea urchin’s skeleton, so that its little weight may serve by its sole presence in your meditations, just as the weight of a human skull attends at every moment those of saints and anchorites. For the latter, since they lived constantly in their ecstasies and celestial ravishments, required the presence of the skull which, like the ballast, held them to their earthly and human condition; while you, painter, live only in those other ecstasies and ravishments which are given to you, on the contrary, by matter and its viscosity. And you will need that blue-tinged skeleton of the sea urchin which, by its lack of weight, will constantly remind you of the celestial regions which the sensuality of your oils and your media might so easily cause you to forget. Thus the mystic who lives only in the celestial paradise bears in his hand a terrestrial skeleton: the skull of man; while the painter who is an Epicurean — for even if he is often a Stoic in his work, he never ceases to live in terrestrial paradises — must bear in his hand the sea urchin, which is like the very skeleton of heaven” (p175-6).

Painter and saint, p174.

“For remember once more that the painter’s head has already been adequately compared, successively and in each of these four chapters to an oil lamp which gives light, to the hump of a ruminant whose mouth is like the eye of a lamp which gives light, to a Bernard hermit who lives within the shell of your skull, and whose red teeth are the arms of the painter which, like a flame of light, also illuminate the picture. And now to give you even more pleasure, I shall without more ado compare this same painter’s head, not to a Bernard the hermit but to a miller who is also, like yourself, a kind of hermit who ruminates and masticates and grinds in the mill of his brain which is the storehouse and attic of reserve images of the camel’s hump; in which the grain of intelligence lies piled, that luminous quintessence, that flow of wheat which is the whiteness of the earth with which you are to knead that daily bread of painting, which thus becomes again the prayer which the painter, with his flour which is the terrestrial luminosity of this world below, daily lifts toward the celestial luminosities of the above. For all the mystery and miraculous humble aspiration of the man painter is nothing less than to make light, radiant and divine, with white and earth colors which are dull and sere” (p150).

Young and adult sea urchin, p108.

A Pedagogical Stunt

January 30th, 2008

A diagram by Joseph Campbell appearing in The Power of Myth, which I have redrawn.

“A pedagogical stunt. Plato has said somewhere that the soul is a circle. I took this idea to suggest on the blackboard the whole sphere of the psyche. Then I drew a horizontal line across the circle to represent the line of separation of the conscious and the unconscious. The dot in the center of the circle, below the horizontal line, represents the center from which all our energy comes… Above the horizontal line is the ego, which I represented as a square: that aspect of our consciousness that we identify as our center. But, you see, it’s very much off center. We think that this is what’s running the show, but it isn’t” (p142).